President Trump's lengthy daily news conferences on the novel coronavirus are an unprecedented leadership strategy for the nation facing a crisis. In no prior national crisis of any sort, have Presidents placed themselves so visibly at the center of all crisis decision-making. This APP analysis provides historical context for current policy by examining the practice of prior presidents in dealing with contagious disease.

We look at two bodies of evidence:

1. The evolution from Washington to Trump of presidential references to contagious disease either by specific disease or by general language about contagious disease.

2. Particular presidential statements reflecting the emergence of a scientific understanding of contagious disease.

Naming Diseases vs. General Concern for Health and Welfare

We have searched all the presidential documents in the APP Database for one of two kinds of language: First is language that explicitly names any of many specific communicable diseases.[1] Explicit disease-naming was almost non-existent prior to the era of scientific understanding of diseases that emerged in the latter part of the 19th century.

Second is general language referring to concern for sickness or disease in documents that have no mention of any specific disease.[2] We might expect a national leader to use this kind of language to express a recognition of these conditions and a sympathy with the experiences of citizens.

The evolution of Presidential practice in naming communicable diseases is shown in this table giving the year of the earliest presidential document in the APP collection with a specific disease reference:

|

Disease |

First Presidential Mention |

President |

Widespread English Use[3] |

|

Cholera |

1833 |

Jackson |

1827 |

|

Yellow Fever |

1860 |

Buchanan |

1820 |

|

Smallpox |

1877 |

Grant |

1820 |

|

Measles |

1886 |

Cleveland |

1813 |

|

Typhoid |

1886 |

Cleveland |

1840 |

|

Plague/Bubonic Plague |

1892 |

Harrison |

1600 |

|

Tuberculosis |

1893 |

Cleveland |

1860 |

|

Leprosy |

1904 |

T. Roosevelt |

1790 |

|

Typhus |

1914 |

Wilson |

1790 |

|

Influenza[4] |

1931 |

Hoover |

1790 |

|

Diphtheria |

1931 |

Hoover |

1855 |

| Infantile Paralysis/ Polio | 1933 | F. D. Roosevelt | 1866 |

|

Scarlet Fever |

1946 |

Truman |

1880 |

|

Whooping cough |

1961 |

Kennedy |

1900 |

|

Ebola |

1983 |

Reagan |

1975 |

|

HIV/AIDS |

1985 |

Reagan |

1983 |

Perhaps the biggest surprise in this table is that there was no reference to "influenza" in 1918, during the great "Spanish Flu" epidemic. We have searched historical newspaper databases to see if the standard collection of presidential papers omits relevant statements or messages. We found no White House or Presidential statements on the subject. In 1918, President Wilson was engaged with financing and managing the successful war effort, starting with his "Fourteen Points" speech in January, and promoting his party in the mid-term elections. There was concern expressed in the press in October that the success of the "Liberty Bond" sale drive should not be harmed by the influenza epidemic.[5]

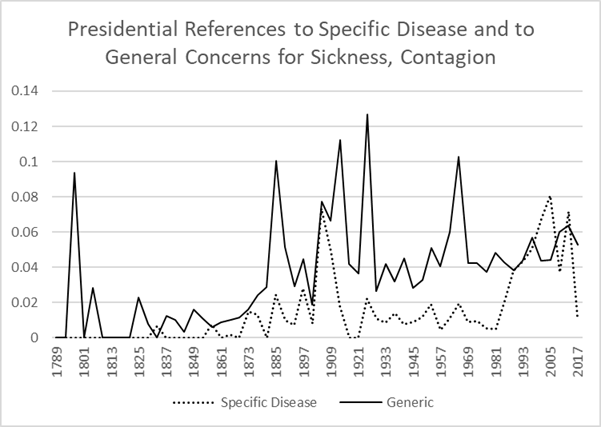

Further findings on presidential language relating to disease are summarized in the graph below. This graph plots the time-path of the proportion of presidential documents with language concerning specific diseases or more general disease references such as illness, pestilence, contagion, or sickness. In both cases, the graph is the annual number of documents with the target referents as a proportion of all presidential documents in the APP collection.

Use of a ratio measure is important in showing the relative attention of presidents to these issues because starting around the 20th century, presidents generated many more documents of all sorts.[6] In this graph, the proportions are averaged over 4-year periods defined by the normal presidential term.

There have been generic expressions of concern about disease throughout the history of the presidency. In the early years, these spike roughly coincident with periods of dreadful epidemics. The references to specific diseases were almost unknown prior to the term of Rutherford B. Hayes (1877), and these too often increase during with dreadful episodes such as HIV/AIDs and Ebola after the 1980s.

In both data series, there is a change that is obvious starting in the late 1800s, reflecting not just a changed role of presidents, but a changed role of the national government with respect to public health and attempts to manage and cure diseases of all sorts.

Presidential Embrace of Scientific Knowledge

The history of presidential leadership in confronting highly contagious disease reflects two primary factors: the evolution of scientific knowledge and the development of a capable body of public servants.

Scientists came to understand the nature and transmission of highly communicable diseases in the middle of the 19th century. Several pioneering epidemiologists studied cholera. Reformers began to build support for "boards of health" and the use of quarantines to control infectious disease. The American Public Health Association was founded in 1872. Under the National Quarantine Act of 1878, the Marine Hospital Service was authorized to prevent possibly infected vessels from entering US ports.

The 20th century saw the combination of a more thorough understanding of the science of infectious diseases together with an appreciation of the implications of vast and growing movements of goods and people across the country and the world. This impelled a more vigorous national regulatory stance.

We can track these developments in statements of US Presidents.

Cholera

Scholars have identified great cholera pandemics in the 19th century, one spanning 1831-32 and another from 1850-1853. In Andrew Jackson's Annual Message of December 4, 1832, his language suggests a sense of being controlled by fate beyond human agency:

Although the pestilence which had traversed the Old World has entered our limits and extended its ravages over much of our land, it has pleased Almighty God to mitigate its severity and lessen the number of its victims compared with those who have fallen in most other countries over which it has spread its terrors.

Similarly in his Third Annual Message, December 6, 1852, Millard Fillmore's stance was also essentially passive:

Our grateful thanks are due to an all-merciful Providence, not only for staying the pestilence which in different forms has desolated some of our cities, but for crowning the labors of the husbandman with an abundant harvest and the nation generally with the blessings of peace and prosperity.

Emergence of Activism: Yellow Fever, Scarlet Fever

The tone is remarkably different a quarter-century later. In his Second Annual Message of December 2, 1878 Rutherford Hayes quotes statistics, describes the mechanism of spreading infection, and speaks of providing relief:

The enjoyment of health by our people generally has, however, been interrupted during the past season by the prevalence of a fatal pestilence (the yellow fever) in some portions of the Southern States, creating an emergency which called for prompt and extraordinary measures of relief. The disease appeared as an epidemic at New Orleans and at other places on the Lower Mississippi soon after midsummer. It was rapidly spread by fugitives from the infected cities and towns, and did not disappear until early in November. The States of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee have suffered severely. About 100,000 cases are believed to have occurred, of which about 20,000, according to intelligent estimates, proved fatal.

The following year, Congress created a National Board of Health, and Hayes's successor Chester A. Arthur was emphatically positive about the new organization in his First Annual Message.

. . . the board was required to institute such measures as might be deemed necessary for preventing the introduction of contagious or infectious diseases from foreign countries into the United States or from one State into another.

The execution of the rules and regulations prepared by the board and approved by my predecessor has done much to arrest the progress of epidemic disease, and has thus rendered substantial service to the nation.

The National Board of Health eventually was disbanded in the face of opposition from state-level health authorities arising from Constitutional ambiguities about National level powers in matters of public health.

The path from 1881 to the present is marked by repeated presidential efforts to promote and consolidate national-level public health authority.

In 1904, Theodore Roosevelt forcefully advocated a national quarantine law.

It is desirable to enact a proper National quarantine law. It is most undesirable that a State should on its own initiative enforce quarantine regulations which are in effect a restriction upon interstate and international commerce. The question should properly be assumed by the Government alone. The Surgeon-General of the National Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service has repeatedly and convincingly set forth the need for such legislation.

In a 1927 address to the American Medical Association Calvin Coolidge praised the benefits business draws from the fact that "medical men" have conquered disease and "robbed them of their terrors."

In 1940, at the dedication of the National Institute of Health facilities in Bethesda, MD, Franklin D. Roosevelt, expressed a confidence in science and an awareness of global disease transmission:

The original demonstration of the cause and method of preventing pellagra, for example, has been followed by other important contributions. Great work has been done in the control of tularemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, typhus fever, yellow fever, malaria, and psittacosis.

Now that we are less than a day by plane from the jungle type yellow fever of South America, less than two days from the sleeping sickness of equatorial Africa, less than three days from cholera and bubonic plague, the ramparts we watch must be civilian in addition to military.

In 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a signing statement praising the passage of the Public Health Service Act. He wrote that "since adequate public health facilities must be organized on a nationwide scale, it is proper that the Federal Government should exercise responsibility of leadership and assistance to the States."

From 1946 to 1983, presidents have issued Executive Orders revising the list of Quarantinable Communicable Diseases, "providing for the apprehension, detention, or conditional release of individuals to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases." (e.g., Reagan's Executive Order 12452).

Through a series of orders, Presidents have directed federal agencies, including HEW and FEMA, to stockpile medical supplies develop national plans for the event of national emergencies. President Bush issued an order creating a National Health Information Technology Coordinator. President Obama issued an Executive Order in 2014 declaring that combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a national security priority. In a 2016 order Obama outlined an agenda to "achieve a world safe and secure from infectious disease threats."

In 2014, President Obama observed, in remarks at the NIH that,

. . . . There may and likely will come a time in which we have both an airborne disease that is deadly. And in order for us to deal with that effectively, we have to put in place an infrastructure—not just here at home, but globally—that allows us to see it quickly, isolate it quickly, respond to it quickly. And it also requires us to continue the same path of basic research that is being done here at the NIH that Nancy [Sullivan] is a great example of. So that if and when a new strain of flu, like the Spanish flu, crops up 5 years from now or a decade from now, we've made the investment, and we're further along to be able to catch it. It is a smart investment for us to make. It's not just insurance, it is knowing that down the road, we're going to continue to have problems like this, particularly in a globalized world, where you move from one side of the world to the other in a day.

Main sources:

Boston University Medical Campus, A Brief History of Public Health. http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/PH/PublicHealthHistory/PublicHealthHistory_print.html

Michael, Jerrold M. 2011. "The National Board of Health: 1879-1883." Public Health Reports 126 (January-February): 123-126. (Online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3001811/)

Rosen, George. 1958, 1993. A History of Public Health (Johns Hopkins University Press)

U.S. Congress. Public Laws of 45th Congress, Sess. II., 1878, Chapter 66 "An act to prevent the introduction of contagious or infectious diseases into the United States" (April 29, 1878.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Inational Institutes of Health. "A Short History of the National Institutes of Health," https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/history/index.html

U.S. Marine Hospital Service of the United States, 1872. "First Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon of the Marine Hospital Service of the United States for the Year 1872. Containing a Brief Historical Sketch of the Service from the Date of its Organization in 1798." Washington: Government Printing Office. (Online at https://books.google.com/books?id=33VUAAAAcAAJ&pg=PP5&dq=marine+hospital+service+first+annual+report+1872&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjSm96smdLoAhVfJTQIHVjdDu4Q6AEwAHoECAMQAg#v=onepage&q=marine%20hospital%20service%20first%20annual%20report%201872&f=false)

U.S. Smithsonian Institution, SI Archives, "Record Unit 7058, National Institute, Records 1839-1863, Collection Overview." https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_217217

[1] Cholera, diphtheria, HIV/AIDS, influenza (including variants mentioned sometimes by name such as H1N1, swine flu, Asian—or "Asiatic"--flu, bird flu, avian flu, etc.), measles, polio, SARS, scarlet fever, smallpox, tuberculosis, typhoid, typhus whooping cough, yellow fever, scarlet fever, plague.

[2]Search terms involve words such as: infectious, sickness, disease, epidemic, pestilence, Illness, infection, sanitation, contagion, contagious, sanitary, when used in documents with none of the prior list of diseases. Obviously many of these words may be used metaphorically.

[3] Roughly the time point of accelerating usage in American English based on Google ngram viewer graphs.

[4] Including searches for more arcane mentions like "the grippe."

[5] Washington Post, "Clerks' Day for Loan" October 15, 1918, p 2.

[6] This approach also adjusts for the fact that at the time of this analysis, the APP database was not completely current with Trump Administration documents