Since the dawn of our republic, Americans have believed our nation was created for a purpose. We were, as Alexander Hamilton said, "a people of great destinies." In the Revolution, the Civil War, in World Wars One and Two, and in the many struggles of the Cold War, our forebears met and overcame threats to our nation's survival and to our way of life. They believed they had a duty to serve a cause greater than their self-interest. They kept faith with the eternal principles of our Declaration of Independence against the evils of despotism, fascism, and totalitarianism. And they changed the world. Democracy was born and then spread across the globe, from North America to Europe to Asia and Latin America, to Africa and the Middle East. Today we stand, grateful, on this foundation of freedom.

Now it is our generation's turn to build. It is our generation's turn to restore and replenish the faith in our nation and our principles. We have suffered terrible attacks at the hands of a new enemy that relentlessly seeks our destruction. New dangers have arisen, great powers are emerging and seek to shift the international balance of power, and we are in the midst of two wars whose outcome will shape our future. Here at home there is discord and doubt, and our famous optimism as a people has begun to flicker. It must not. Ever since Jamestown, we have displayed courage in the face of adversity. We are a hardy, spirited and steadfast people, a nation of pioneers and inveterate problem solvers. Today, America remains the most attractive of nations, where people the world over wish to visit, study, live, start businesses, invest and look for inspiration in our values and our freedoms. That is why I believe we are about to enter our greatest and proudest years as a nation.

Our great president, Harry Truman once said of America, "God has created us and brought us to our present position of power and strength for some great purpose." In his time, that great purpose was to erect structures of peace and prosperity that could provide safe passage through the Cold War. Today, we face new dangers and new opportunities and we must have a new common mission: To build an enduring global peace, and to build it upon the foundations of freedom, opportunity, prosperity and hope.

There is so much promise in today's world. We live in an era of unprecedented human progress. An increasingly global commerce is spreading a better and freer life to millions. Our scientists and physicians are eradicating diseases that once ravaged populations. More people live under democracy than at any time in human history. More than ever before, a father and mother can pass on to their children a happier, healthier, longer, and freer life than they themselves knew. Yet as we seize and expand these opportunities, we must recognize the dangers posed by the forces of terrorism and tyranny that look backward into a world of darkness and violence. With our democratic friends and allies around the world, we need to build a new global order of peace, a peace that can last not just for a decade but for a century, where the dangers and threats we face diminish, and where human progress reaches new heights.

Almost two centuries ago James Madison declared that the great struggle of the Epoch "was between liberty and despotism." Many thought that this struggle ended with the Cold War, but it didn't. It took on new guises, such as the modern terrorist network, an enemy of progress that has turned our technological advances to its own use, and in rulers trying to rebuild 19th-century autocracies in a 21st century world. Today the talk is of the war on terror, a war in which we must succeed. But the war on terror cannot be the only organizing principle of American foreign policy. International terrorists capable of inflicting mass destruction are a new phenomenon. But what they seek and what they stand for are as old as time. They comprise part of worldwide political, economic, and philosophical struggle between the future and the past, between progress and reaction, and between liberty and despotism. Upon the outco me of that struggle depends our security, our prosperity, and our democratic way of life.

Democracy and freedom continue to flourish around the world, but there have been some discouraging trends. In China, despite miraculous economic growth and a higher standard of living for many millions of Chinese, hopes for an accompanying political reform have diminished. The ruling party seems determined to dominate political life, and as in the past, the talk is of order, not democracy, the supremacy of the party not of the people. China astonishes the world with its economic and technological modernization, but then spends billions trying to control that great icon of the modern era, the internet. China recognizes its vital interest in economic integration with the democratic world. But it has also joined Russia in hindering international efforts to put pressure on dictators in Iran, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Burma, and other pariah states. China expresses its desire for a stable peace in East Asia, but it contin ues to increase its military might, fostering distrust and concerns in the region about Beijing's ambitions. We must insist that China use its newfound power responsibly at home and abroad.

A decade ago, the great Russian people had thrown off communist tyranny and seemed determined to build democracy and a free market and to join the West. Today, Russia looks more and more like some 19th-century autocracy, marked by diminishing political freedoms, shadowy intrigue, and mysterious assassinations. Beyond its borders Moscow has tried to expand its influence over its neighbors in Eastern, Central and even Western Europe. While the more democratic Russia of the 1990s sought to deepen its ties with Europe and America, today a more authoritarian Moscow manipulates Europe's dependence on Russian oil and gas to compel silence and obedience, and to try to drive a wedge between Europe and the United States. The Russian government is even more brutal toward the young democracies on its periphery, threatening them with trade embargoes and worse if they move too close to the West. It supports separatist mov ements in Georgia and Moldova and openly intervened in Ukraine's presidential elections. And it is supplying weapons to Iran, Syria, and indirectly to Hezbollah.

But if some in Russia yearn to turn the clock back two decades, the zealots of Islamic radicalism would turn it back centuries. The mullahs of Iran and the leaders of Al Qaeda and Hezbollah want to cleanse the Muslim world of modernity and the ideals of the Enlightenment, and return it to an imagined past of theological purity. They state their goal plainly: a universal Islamic theocracy, a new Caliphate across all the lands once dominated by Islam, including the lands held in Europe centuries ago. Meanwhile, Mideast autocracies fuel this radicalism by denying their people political expression, economic opportunity or hope for a better future.

These governments differ from one another in a thousand ways, and our policies toward them must reflect those differences. Our national interests require that we pursue economic and strategic cooperation with China and Russia, that we support Egypt and Saudi Arabia's role as peacemakers in the Middle East, and that we work with Pakistan to fight the Taliban and Al Qaeda. But our national interests also require that we continually press for progress.

We have seen how autocratic governments often work against our interests. Iran is able to aggressively pursue nuclear weapons and hegemony in the Persian Gulf, in part, because it has been shielded by the world's powerful autocracies. North Korea defies the international community with its nuclear weapons and missile programs and an obscene human rights record. Last month, North Korea unsurprisingly missed the first deadline in the most recent nuclear agreement and it remains to be seen if China will use its enormous influence to demand better behavior.

The path to an enduring peace lies in a clear-eyed pursuit of our national interest that does not accede to autocratic trends. We must expand the power and reach of democracy, freedom, and human rights using our many strengths as a free people. But that means making some substantial changes in how we do business. Change must begin at home.

Back in 1947, just a year into the Cold War, the Truman administration launched a massive overhaul of the nation's foreign policy, defense, and intelligence agencies to meet new challenges. Today, we must do the same to meet the challenges of the 21st century. I will have much more to say about this in the future but our needs are clear in the organization, skills, and capabilities needed to prevail in the conflict with violent extremists: an intelligence community that is able to collect and analyze information on and conduct operations against our enemies; a public diplomacy effort that makes our case to the world effectively; a diplomatic corps that understands stability does not mean supporting dictatorships; foreign aid programs that foster good governance; generals that understand and learn from past wars and apply those lessons to the future; defense procurement that is transparent, accountable and e ffective; and civilian defense leadership that is held accountable for results and provides the resources necessary to achieve results. We must never again launch a military operation with too few troops to complete the mission and build a secure, stable, and democratic peace. When we fight a war, we must fight to win.

We cannot build an enduring peace based on freedom by ourselves. Nor do we want to. The Declaration of Independence proclaimed our duty to pay decent respect to the opinions of mankind. When I think back to the 1980s, the decade of triumph in the Cold War, I think about our great alliances. Reagan, Thatcher, Kohl, Mitterrand, Nakasone they were all strong leaders who jealously guarded the interests of their peoples. But they linked arms against communist tyranny.

Today we need to revive that vital democratic solidarity. We need to renew the terms of our partnership and strike a new grand bargain for the future. We Americans must be willing to listen to the views and respect the collective will of our democratic allies. Like all other nations, we reserve the sovereign right to defend our vital national security when and how we deem necessary. But our great power does not mean we can do whatever we want whenever we want, nor should we assume we have all the wisdom, knowledge and resources necessary to succeed. When we believe international action is necessary, whether military, economic, or diplomatic, we must work to persuade our democratic friends and allies that we are right. But in return, we must be willing to be persuaded by them. To be a good leader, America must be a good ally.

Our partners must be good allies, too. They must have the will and the ability to act in the common defense of freedom, democracy, and economic prosperity. They must spend the money necessary to build effective militaries that can train and fight alongside ours. They must help us deliver aid to those in need and encourage good governance in fragile states. They must face the threats of our world squarely and not evade their global responsibilities. And they must put an end to the mindless anti-Americanism that today mars international discourse. No alliance can work unless all its members share a basic faith in one another and accept an equal share of the responsibility to build a peace based on freedom.

If we strike this new bargain and renew our transatlantic solidarity, I believe we must then take the next step and expand the circle of our democratic community. As we speak, American soldiers are serving in Afghanistan alongside British, Canadian, Dutch, German, Italian, Spanish, Turkish, Polish, and Lithuanian soldiers from the NATO alliance. They are also serving alongside forces from Australia, New Zealand, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea --all democratic allies or close partners of the United States. But they are not all part of a common structure. They don't work together systematically or meet regularly to develop diplomatic and economic strategies to meet their common problems. The 21st century world no longer divides neatly into geographic regions. Organizations and partnerships must be as international as the challenges we confront.

The NATO alliance has begun to deal with this gap by promoting global partnerships between current members of the alliance and the other great democracies in Asia and elsewhere. We should go further and start bringing democratic peoples and nations from around the world into one common organization, a worldwide League of Democracies. This would not be like the universal-membership and failed League of Nations' of Woodrow Wilson but much more like what Theodore Roosevelt envisioned: like-minded nations working together in the cause of peace. The new League of Democracies would form the core of an international order of peace based on freedom. It could act where the UN fails to act, to relieve human suffering in places like Darfur. It could join to fight the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa and fashion better policies to confront the crisis of our environment. It could provide unimpeded market access to t hose who share the values of economic and political freedom, an advantage no state-based system could attain. It could bring concerted pressure to bear on tyrants in Burma or Zimbabwe, with or without Moscow's and Beijing's approval. It could unite to impose sanctions on Iran and thwart its nuclear ambitions. It could provide support to struggling democracies in Ukraine and Serbia and help countries like Thailand back on the path to democracy.

This League of Democracies would not supplant the United Nations or other international organizations. It would complement them. But it would be the one organization where the world's democracies could come together to discuss problems and solutions on the basis of shared principles and a common vision of the future. If I am elected president, I will call a summit of the world's democracies in my first year to seek the views of my democratic counterparts and begin exploring the practical steps necessary to realize this vision.

Americans should lead this effort, as we did sixty years ago in founding NATO. But if we are to lead responsibly, our friends and allies must see us as responsible nation, concerned not only about our own well-being but about the health of the world's economy and the future of our planet.

Throughout the Cold War, America's support for a global economic system based on free trade and free flows of capital went hand-in-hand with our support of political freedom and democracy. To build a new era of peace based on freedom, we have to work even harder through our economic and trade policies to encourage open societies and create a climate of opportunity and hope. Our economic strategies in the Middle East must complement our political strategies by supporting modernizers who want to improve the lives of their people against those radicals and autocrats who would impoverish them. In Latin America and Africa, we need to support those who favor open economies and democratic government against populist demagogues who are dragging their nations back to the failed socialist policies of the past. In Asia we need to show that growing democratic economies can do more for the average man and woman and less for corrupt senior officials than growing economies in a one-party state.

Americans are the most generous and caring people in the world. No one has sacrificed more in lives and treasure to save the world from tyranny. No nation spends more in combined public and private philanthropic efforts to combat disease and poverty around the world. And no one works harder to ensure the continued health and vitality of the global economy.

Still, there is more we can do. To be successful international leaders, we need to be good international citizens. This means upholding and strengthening international laws and norms, including the laws of war. We must champion the Geneva Conventions, and we must fulfill the letter and the spirit of our international obligations. It is profoundly in our interest to do so, since our failure to abide by these rules puts our own soldiers at risk. Our moral standing in the world requires that we respect what are, after all, American principles of justice. Our values will always triumph in any war of ideas, and we can't let failings like prisoner abuse tarnish our image. If we are model citizens of the world, more people around the world will look to us as a model.

When our nation was founded over two hundred years ago, we were the world's only democratic republic. Today, there are more than 100 electoral democracies spread all across the globe. We must reaffirm our faith in the principles that our founders declared to be universal, that all people are created equal and possess inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We fought a Revolution, a Civil War, two world wars, and a cold war to vindicate these principles and ensure that freedom could be enjoyed, as Abraham Lincoln promised, by all "people of all colors everywhere." We were right to struggle for democracy then, and we are right to do so now.

This is not idealism, my friends. It is the truest kind of realism. Today as in the past, our interests are inextricably linked to the global progress of our ideals. The vision of a new era of enduring peace based on freedom is not a Republican vision. It is not a Democratic vision. It is an American vision. The American people have known instinctively for two centuries that we are safer when the world is more democratic. Whatever our differences, we all share the same goal: a world of peace and freedom, of prosperity and opportunity, of hope. We have a duty to ourselves to be true to those beliefs, to use our great power wisely on behalf of freedom. As Ronald Reagan proclaimed in his speech to the British Parliament in 1982, "Let us go to our strength. Let us offer hope. Let us tell the world that a new age is not only possible but probable."

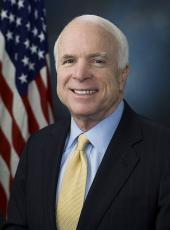

John McCain, Address at the Hoover Institution on U.S. Foreign Policy Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/277688