To the Congress:

The rejection by the Senate of the treaty lately negotiated for the settlement and adjustment of the differences existing between the United States and Great Britain concerning the rights and privileges of American fishermen in the ports and waters of British North America seems to justify a survey of the condition to which the pending question is thus remitted.

The treaty upon this subject concluded in 1818, through disagreements as to the meaning of its terms, has been a fruitful source of irritation and trouble. Our citizens engaged in fishing enterprises in waters adjacent to Canada have been subjected to numerous vexatious interferences and annoyances; their vessels have been seized upon pretexts which appeared to be entirely inadmissible, and they have been otherwise treated by the Canadian authorities and officials in a manner inexcusably harsh and oppressive.

This conduct has been justified by Great Britain and Canada by the claim that the treaty of 1818 permitted it and upon the ground that it was necessary to the proper protection of Canadian interests. We deny that treaty agreements justify these acts, and we further maintain that aside from any treaty restraints of disputed interpretation the relative positions of the United States and Canada as near neighbors, the growth of our joint commerce, the development and prosperity of both countries, which amicable relations surely guarantee, and, above all, the liberality always extended by the United States to the people of Canada furnished motives for kindness and consideration higher and better than treaty covenants.

While keenly sensitive to all that was exasperating in the condition and by no means indisposed to support the just complaints of our injured citizens, I still deemed it my duty, for the preservation of important American interests which were directly involved, and in view of all the details of the situation, to attempt by negotiation to remedy existing wrongs and to finally terminate by a fair and just treaty these ever-recurring causes of difficulty.

I fully believe that the treaty just rejected by the Senate was well suited to the exigency, and that its provisions were adequate for our security in the future from vexatious incidents and for the promotion of friendly neighborhood and intimacy, without sacrificing in the least our national pride or dignity.

I am quite conscious that neither my opinion of the value of the rejected treaty nor the motives which prompted its negotiation are of importance in the light of the judgment of the Senate thereupon. But it is of importance to note that this treaty has been rejected without any apparent disposition on the part of the Senate to alter or amend its provisions, and with the evident intention, not wanting expression, that no negotiation should at present be concluded touching the matter at issue.

The cooperation necessary for the adjustment of the long-standing national differences with which we have to deal by methods of conference and agreement having thus been declined, I am by no means disposed to abandon the interests and the rights of our people in the premises or to neglect their grievances; and I therefore turn to the contemplation of a plan of retaliation as a mode which still remains of treating the situation.

I am not unmindful of the gravity of the responsibility assumed in adopting this line of conduct, nor do I fail in the least to appreciate its serious consequences. It will be impossible to injure our Canadian neighbors by retaliatory measures without inflicting some damage upon our own citizens. This results from our proximity, our community of interests, and the inevitable commingling of the business enterprises which have been developed by mutual activity.

Plainly stated, the policy of national retaliation manifestly embraces the infliction of the greatest harm upon those who have injured us, with the least possible damage to ourselves. There is also an evident propriety, as well as an invitation to moral support, found in visiting upon the offending party the same measure or kind of treatment of which we complain, and as far as possible within the same lines. And above all things, the plan of retaliation, if entered upon, should be thorough and vigorous.

These considerations lead me at this time to invoke the aid and counsel of the Congress and its support in such a further grant of power as seems to me necessary and desirable to render effective the policy I have indicated.

The Congress has already passed a law, which received Executive assent on the 3d day of March, 1887, providing that in case American fishing vessels, being or visiting in the waters or at any of the ports of the British dominions of North America, should be or lately had been deprived of the rights to which they were entitled by treaty or law, or if they were denied certain other privileges therein specified or vexed and harassed in the enjoyment of the same, the President might deny to vessels and their masters and crews of the British dominions of North America any entrance into the waters, ports, or harbors of the United States, and also deny entry into any port or place of the United States of any product of said dominions or other goods coming from said dominions to the United States.

While I shall not hesitate upon proper occasion to enforce this act, it would seem to be unnecessary to suggest that if such enforcement is limited in such a manner as shall result in the least possible injury to our own people the effect would probably be entirely inadequate to the accomplishment of the purpose desired.

I deem it my duty, therefore, to call the attention of the Congress to certain particulars in the action of the authorities of the Dominion of Canada, in addition to the general allegations already made, which appear to be in such marked contrast to the liberal and friendly disposition of our country as in my opinion to call for such legislation as will, upon the principles already stated, properly supplement the power to inaugurate retaliation already vested in the Executive.

Actuated by the generous and neighborly spirit which has characterized our legislation, our tariff laws have since 1866 been so far waived in favor of Canada as to allow free of duty the transit across the territory of the United States of property arriving at our ports and destined to Canada, or exported from Canada to other foreign countries.

When the treaty of Washington was negotiated, in 1871, between the United States and Great Britain, having for its object very largely the modification of the treaty of 1818, the privileges above referred to were made reciprocal and given in return by Canada to the United States in the following language, contained in the twenty-ninth article of said treaty:

It is agreed that for the term of years mentioned in Article XXXIII of this treaty goods, wares, or merchandise arriving at the ports of New York, Boston, and Portland, and any other ports in the United States which have been or may from time to time be specially designated by the President of the United States, and destined for Her Britannic Majesty's possessions in North America, may be entered at the proper custom-house and conveyed in transit, without the payment of duties, through the territory of the United States, under such rules, regulations, and conditions for the protection of the revenue as the Government of the United States may from time to time prescribe; and, under like rules, regulations, and conditions, goods, wares, or merchandise may be conveyed in transit, without the payment of duties, from such possessions through the territory of the United States, for export from the said ports of the United States.

It is further agreed that for the like period goods, wares, or merchandise arriving at any of the ports of Her Britannic Majesty's possessions in North America, and destined for the United States, may be entered at the proper custom-house and conveyed in transit, without the payment of duties, through the said possessions, under such rules and regulations and conditions for the protection of the revenue as the governments of the said possessions may from time to time prescribe; and, under like rules, regulations, and conditions, goods, wares, or merchandise may be conveyed in transit, without payment of duties, from the United States through the said possessions to other places in the United States, or for export from ports in the said possessions.

In the year 1886 notice was received by the representatives of our Government that our fishermen would no longer be allowed to ship their fish in bond and free of duty through Canadian territory to this country, and ever since that time such shipment has been denied.

The privilege of such shipment, which had been extended to our fishermen, was a most important one, allowing them to spend the time upon the fishing grounds which would otherwise be devoted to a voyage home with their catch, and doubling their opportunities for profitably prosecuting their vocation.

In forbidding the transit of the catch of our fishermen over their territory in bond and free of duty the Canadian authorities deprived us of the only facility dependent upon their concession and for which we could supply no substitute.

The value to the Dominion of Canada of the privilege of transit for their exports and imports across our territory and to and from our ports, though great in every aspect, will be better appreciated when it is remembered that for a considerable portion of each year the St. Lawrence River, which constitutes the direct avenue of foreign commerce leading to Canada, is closed by ice.

During the last six years the imports and exports of British Canadian provinces carried across our territory under the privileges granted by our laws amounted in value to about $270,000,000, nearly all of which were goods dutiable under our tariff laws, by far the larger part of this traffic consisting of exchanges of goods between Great Britain and her American Provinces brought to and carried from our ports in their own vessels.

The treaty stipulation entered into by our Government was in harmony with laws which were then on our statute book and are still in force.

I recommend immediate legislative action conferring upon the Executive the power to suspend by proclamation the operation of all laws and regulations permitting the transit of goods, wares, and merchandise in bond across or over the territory of the United States to or from Canada.

There need be no hesitation in suspending these laws arising from the supposition that their continuation is secured by treaty obligations, for it seems quite plain that Article XXIX of the treaty of 1871, which was the only article incorporating such laws, terminated the 1st day of July, 1885.

The article itself declares that its provisions shall be in force "for the term of years mentioned in Article XXXIII of this treaty." Turning to Article XXXIII, we find no mention of the twenty-ninth article, but only a provision that Articles XVIII to XXV, inclusive, and Article XXX shall take effect as soon as the laws required to carry them into operation shall be passed by the legislative bodies of the different countries concerned, and that "they shall remain in force for the period of ten years from the date at which they may come into operation, and, further, until the expiration of two years after either of the high contracting parties shall have given notice to the other of its wish to terminate the same."

I am of the opinion that the "term of years mentioned in Article XXXIII," referred to in Article XXIX as the limit of its duration, means the period during which Articles XVIII to XXV, inclusive, and Article XXX, commonly called the "fishery articles," should continue in force under the language of said Article XXXIII.

That the joint high commissioners who negotiated the treaty so understood and intended the phrase is certain, for in a statement containing an account of their negotiations, prepared under their supervision and approved by them, we find the following entry on the subject:

The transit question was discussed, and it was agreed that any settlement that might be made should include a reciprocal arrangement in that respect for the period for which the fishery articles should be in force.

In addition to this very satisfactory evidence supporting this construction of the language of Article XXIX, it will be found that the law passed by Congress to carry the treaty into effect furnishes conclusive proof of the correctness of such construction.

This law was passed March 1, 1873, and is entitled "An act to carry into effect the provisions of the treaty between the United States and Great Britain signed in the city of Washington the 8th day of May, 1871, relating to the fisheries." After providing in its first and second sections for putting in operation Articles XVIII to XXV, inclusive, and Article XXX of the treaty, the third section is devoted to Article XXIX, as follows:

SEC. 3. That from the date of the President's proclamation authorized by the first section of this act, and so long as the articles eighteenth to twenty-fifth, inclusive, and article thirtieth of said treaty shall remain in force according to the terms and conditions of article thirty-third of said treaty, all goods, wares, and merchandise, arriving-- etc., etc., following in the remainder of the section the precise words of the stipulation on the part of the United States as contained in Article XXIX, which I have already fully quoted.

Here, then, is a distinct enactment of the Congress limiting the duration of this article of the treaty to the time that Articles XVIII to XXV, inclusive, and Article XXX should continue in force. That in fixing such limitation it but gave the meaning of the treaty itself is indicated by the fact that its purpose is declared to be to carry into effect the provisions of the treaty, and by the further fact that this law appears to have been submitted before the promulgation of the treaty to certain members of the joint high commission representing both countries, and met with no objection or dissent.

There appearing to be no conflict or inconsistency between the treaty and the act of the Congress last cited, it is not necessary to invoke the well-settled principle that in case of such conflict the statute governs the question.

In any event, and whether the law of 1873 construes the treaty or governs it, section 29 of such treaty, I have no doubt, terminated with the proceedings taken by our Government to terminate Articles XVIII to XXV, inclusive, and Article XXX of the treaty. These proceedings had their inception in a joint resolution of Congress passed May 3, 1883, declaring that in the judgment of Congress these articles ought to be terminated, and directing the President to give the notice to the Government of Great Britain provided for in Article XXXIII of the treaty. Such notice having been given two years prior to the 1st day of July, 1885, the articles mentioned were absolutely terminated on the last-named day, and with them Article XXIX was also terminated.

If by any language used in the joint resolution it was intended to relieve section 3 of the act of 1873, embodying Article XXIX of the treaty, from its own limitations, or to save the article itself, I am entirely satisfied that the intention miscarried.

But statutes granting to the people of Canada the valuable privileges of transit for their goods from our ports and over our soil, which had been passed prior to the making of the treaty of 1871 and independently of it, remained in force; and ever since the abrogation of the treaty, and notwithstanding the refusal of Canada to permit our fishermen to send their fish to their home market through her territory in bond, the people of that Dominion have enjoyed without diminution the advantages of our liberal and generous laws.

Without basing our complaint upon a violation of treaty obligations, it is nevertheless true that such refusal of transit and the other injurious acts which have been recited constitute a provoking insistence upon rights neither mitigated by the amenities of national intercourse nor modified by the recognition of our liberality and generous considerations.

The history of events connected with this subject makes it manifest that the Canadian government can, if so disposed administer its laws and protect the interests of its people without manifestation of unfriendliness and without the unneighborly treatment of our fishing vessels of which we have justly complained, and whatever is done on our part should be done in the hope that the disposition of the Canadian government may remove the occasion of a resort to the additional executive power now sought through legislative action.

I am satisfied that upon the principles which should govern retaliation our intercourse and relations with the Dominion of Canada furnish no better opportunity for its application than is suggested by the conditions herein presented, and that it could not be more effectively inaugurated than under the power of suspension recommended.

While I have expressed my clear conviction upon the question of the continuance of section 29 of the treaty of 1871, I of course fully concede the power and the duty of the Congress, in contemplating legislative action, to construe the terms of any treaty stipulation which might upon any possible consideration of good faith limit such action, and likewise the peculiar propriety in the case here presented of its interpretation of its own language, as contained in the laws of 1873 putting in operation said treaty and of 1883 directing the termination thereof; and if in the deliberate judgment of Congress any restraint to the proposed legislation exists, it is to be hoped that the expediency of its early removal will be recognized.

I desire also to call the attention of the Congress to another subject involving such wrongs and unfair treatment to our citizens as, in my opinion, require prompt action.

The navigation of the Great Lakes and the immense business and carrying trade growing out of the same have been treated broadly and liberally by the United States Government and made free to all mankind, while Canadian railroads and navigation companies share in our country's transportation upon terms as favorable as are accorded to our own citizens.

The canals and other public works built and maintained by the Government along the line of the lakes are made free to all.

In contrast to this condition, and evincing a narrow and ungenerous commercial spirit, every lock and canal which is a public work of the Dominion of Canada is subject to tolls and charges.

By Article XXVII of the treaty of 1871 provision was made to secure to the citizens of the United States the use of the Welland, St. Lawrence, and other canals in the Dominion of Canada on terms of equality with the inhabitants of the Dominion, and to also secure to the subjects of Great Britain the use of the St. Clair Flats Canal on terms of equality with the inhabitants of the United States.

The equality with the inhabitants of the Dominion which we were promised in the use of the canals of Canada did not secure to us freedom from tolls in their navigation, but we had a right to expect that we, being Americans and interested in American commerce, would be no more burdened in regard to the same than Canadians engaged in their own trade; and the whole spirit of the concession made was, or should have been, that merchandise and property transported to an American market through these canals should not be enhanced in its cost by tolls many times higher than such as were carried to an adjoining Canadian market. All our citizens, producers and consumers as well as vessel owners, were to enjoy the equality promised.

And yet evidence has for some time been before the Congress, furnished by the Secretary of the Treasury, showing that while the tolls charged in the first instance are the same to all, such vessels and cargoes as are destined to certain Canadian ports are allowed a refund of nearly the entire tolls, while those bound for American ports are not allowed any such advantage.

To promise equality, and then in practice make it conditional upon our vessels doing Canadian business instead of their own, is to fulfill a promise with the shadow of performance.

I recommend that such legislative action be taken as will give Canadian vessels navigating our canals, and their cargoes, precisely the advantages granted to our vessels and cargoes upon Canadian canals, and that the same be measured by exactly the same rule of discrimination.

The course which I have outlined and the recommendations made relate to the honor and dignity of our country and the protection and preservation of the rights and interests of all our people. A government does but half its duty when it protects its citizens at home and permits them to be imposed upon and humiliated by the unfair and overreaching disposition of other nations. If we invite our people to rely upon arrangements made for their benefit abroad, we should see to it that they are not deceived; and if we are generous and liberal to a neighboring country, our people should reap the advantage of it by a return of liberality and generosity.

These are subjects which partisanship should not disturb or confuse. Let us survey the ground calmly and moderately; and having put aside other means of settlement, if we enter upon the policy of retaliation let us pursue it firmly, with a determination only to subserve the interests of our people and maintain the high standard and the becoming pride of American citizenship.

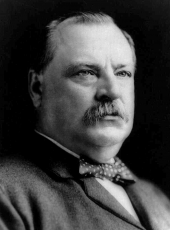

GROVER CLEVELAND

Grover Cleveland, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/206191