To the Senate and House of Representatives:

In compliance with the request of a large number of intelligent and benevolent citizens, and believing that it was warranted by the extraordinary circumstances of the case, on the 18th day of December, 1880, I appointed a commission consisting of George Crook and Nelson A. Miles, brigadier-generals in the Army; William Stickney, of the District of Columbia, and Walter Allen, of Massachusetts, and requested them to confer with the Ponca Indians in the Indian Territory, and, if in their judgment it was advisable, also with that part of the tribe which remained in Dakota, and "to ascertain the facts in regard to their removal and present condition so far as was necessary to determine the question as to what justice and humanity required should be done by the Government of the United States, and to report their conclusions and recommendations in the premises."

The commission, in pursuance of these instructions, having visited the Ponca Indians at their homes in the Indian Territory and in Dakota and made a careful investigation Of the subject referred to them, have reported their conclusions and recommendations, and I now submit their report, together with the testimony taken, for the consideration of Congress. A minority report by Mr. Allen is also herewith submitted.

On the 27th of December, 1880, a delegation of Ponca chiefs from the Indian Territory presented to the Executive a declaration of their wishes, in which they stated that it was their desire "to remain on the lands now occupied by the Poncas in the Indian Territory" and "to relinquish all their right and interest in the lands formerly owned and occupied by the Ponca tribe in the State of Nebraska and the Territory of Dakota;" and the declaration sets forth the compensation which they will accept for the lands to be surrendered and for the injuries done to the tribe by their removal to the Indian Territory. This declaration, agreeably to the request of the chiefs making it, is herewith transmitted to Congress.

The public attention has frequently been called to the injustice and wrong which the Ponca tribe of Indians has suffered at the hands of the Government of the United States. This subject was first brought before Congress and the country by the Secretary of the Interior in his annual report for the year 1877, in which he said:

The case of the Poncas seems entitled to especial consideration at the hands of Congress. They have always been friendly to the whites. It is said, and, as far as I have been able to learn, truthfully, that no Ponca ever killed a white man. The orders of the Government have always met with obedient compliance at their hands. Their removal from their old homes on the Missouri River was to them a great hardship. They had been born and raised there. They had houses there in which they lived according to their ideas of comfort. Many of them had engaged in agriculture and possessed cattle and agricultural implements. They were very reluctant to leave all this, but when Congress had resolved upon their removal they finally overcame that reluctance and obeyed. Considering their constant good conduct, their obedient spirit, and the sacrifices they have made, they are certainly entitled to more than ordinary care at the hands of the Government, and I urgently recommend that liberal provision be made to aid them in their new settlement.

In the same volume the report of E. A. Howard, the agent of the Poncas, is published, which contains the following:

I am of the opinion that the removal of the Poncas from the northern climate of Dakota to the southern climate of the Indian Territory at the season of the year it was done will prove a mistake, and that a great mortality will surely follow among the people when they shall have been here for a time and become poisoned with the malaria of the climate. Already the effects of the climate may be seen upon them in the ennui that seems to have settled upon each and in the large number now sick.

It is a matter of astonishment to me that the Government should have ordered the removal of the Ponca Indians from Dakota to the Indian Territory without having first made some provision for their settlement and comfort. Before their removal was carried into effect an appropriation should have been made by Congress sufficient to have located them in their new home, by building a comfortable house for the occupancy of every family of the tribe. As the case now is, no appropriation has been made by Congress, except for a sum but little more than sufficient to remove them; no houses have been built for their use, and the result is that these people have been placed on an uncultivated reservation to live in their tents as best they may, and await further legislative action.

These Indians claim that the Government had no right to move them from their reservation without first obtaining from them by purchase or treaty the title which they had acquired from the Government, and for which they rendered a valuable consideration. They claim that the date of the settlement of their tribe upon the land composing their old reservation is prehistoric; that they were all born there, and that their ancestors from generations back beyond their knowledge were born and lived upon its soil, and that they finally acquired a complete and perfect title from the Government by a treaty made with the "Great Father" at Washington, which they claim made it as legitimately theirs as is the home of the white man acquired by gift or purchase.

The subject was again referred to in similar terms in the annual report of the Interior Department for 1878, in the reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and of the agent for the Poncas, and in 1879 the Secretary of the Interior said:

That the Poncas were grievously wronged by their removal from their location on the Missouri River to the Indian Territory, their old reservation having, by a mistake in making the Sioux treaty, been transferred to the Sioux, has been at length and repeatedly set forth in my reports, as well as those of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. All that could be subsequently done by this Department in the absence of new legislation to repair that wrong and to indemnify them for their losses has been done with more than ordinary solicitude. They were permitted to select a new location for themselves in the Indian Territory, the Quapaw Reserve, to which they had first been taken, being objectionable to them. They chose a tract of country on the Arkansas River and the Salt Fork northwest of the Pawnee Reserve. I visited their new reservation personally to satisfy myself of their condition. The lands they now occupy are among the very best in the Indian Territory in point of fertility, well watered and well timbered, and admirably adapted for agriculture as well as stock raising. In this respect their new reservation is unquestionably superior to that which they left behind them on the Missouri River. Seventy houses have been built by and for them, of far better quality than the miserable huts they formerly occupied in Dakota, and the construction of a larger number is now in progress, so that, as the agent reports, every Ponca family will be comfortably housed before January. A very liberal allowance of agricultural implements and stock cattle has been given them, and if they apply themselves to agricultural work there is no doubt that their condition will soon be far more prosperous than it has ever been before. During the first year after their removal to the Indian Territory they lost a comparatively large number of their people by death, in consequence of the change of climate, which is greatly to be deplored; but their sanitary condition is now very much improved. The death rate among them during the present year has been very low, and the number of eases of sickness is constantly decreasing. It is thought that they are now sufficiently acclimated to be out of danger.

A committee of the Senate, after a very full investigation of the subject, on the 31st of May, 1880, reported their conclusions to the Senate, and both the majority and minority of the committee agreed that "a great wrong had been done to the Ponca Indians." The majority of the committee say:

Nothing can strengthen the Government in a just policy to the Indians so much as a demonstration of its willingness to do ample and complete justice whenever it can be shown that it has inflicted a wrong upon a weak and trusting tribe. It is impossible for the United States to hope for any confidence to be reposed in them by the Indians until there shall be shown on their part a readiness to do justice.

The minority report is equally explicit as to the duty of the Government to repair the wrong done the Poncas. It says:

We should be more prompt and anxious because they are weak and we are strong. In my judgment we should be liberal to the verge of lavishness in the expenditure of our money to improve their condition, so that they and all others may know that, although, like all nations and all men, we may do wrong, we are willing to make ample reparation.

The report of the commission appointed by me, of which General Crook was chairman, and the testimony taken by them and their investigations, add very little to what was already contained in the official reports of the Secretary of the Interior and the report of the Senate committee touching the injustice done to the Poncas by their removal to the Indian Territory. Happily, however, the evidence reported by the commission and their recommendations point out conclusively the true measures of redress which the Government of the United States ought now to adopt.

The commission in their conclusions omit to state the important facts as to the present condition of the Poncas in the Indian Territory, but the evidence they have reported shows clearly and conclusively that the Poncas now residing in that Territory, 521 in number, are satisfied with their new homes; that they are healthy, comfortable, and contented, and that they have freely and firmly decided to adhere to the choice announced in their letter of October 25, 1880, and in the declaration of December 1880, to remain in the Indian Territory and not to return to Dakota.

The evidence reported also shows that the fragment of the Ponca tribe--perhaps 150 in number--which is still in Dakota and Nebraska prefer to remain on their old reservation.

In view of these facts I am convinced that the recommendations of the commission, together with the declaration of the chiefs of December last, if substantially followed, will afford a solution of the Ponca question which is consistent with the wishes and interests of both branches of the tribe, with the settled Indian policy of the Government, and, as nearly as is now practicable, with the demands of justice.

Our general Indian policy for the future should embrace the following leading ideas:

1. The Indians should be prepared for citizenship by giving to their young of both sexes that industrial and general education which is required to enable them to be self-supporting and capable of self-protection in a civilized community.

2. Lands should be allotted to the Indians in severalty, inalienable for a certain period.

3. The Indians should have a fair compensation for their lands not required for individual allotments, the amount to be invested, with suitable safeguards, for their benefit.

4. With these prerequisites secured, the Indians should be made citizens and invested with the rights and charged with the responsibilities of citizenship.

It is therefore recommended that legislation be adopted in relation to the Ponca Indians, authorizing the Secretary of the Interior to secure to the individual members of the Ponca tribe, in severalty, sufficient land for their support. inalienable for a term of years and until the restriction upon alienation may be removed by the President. Ample time and opportunity should be given to the members of the tribe freely to choose their allotments either on their old or their new reservation.

Full compensation should be made for the lands to be relinquished, for their losses by the Sioux depredations and by reason of their removal to the Indian Territory, the amount not to be less than the sums named in the declaration of the chiefs made December 27, 1880.

In short, nothing should be left undone to show to the Indians that the Government of the United States regards their rights as equally sacred with those of its citizens.

The time has come when the policy should be to place the Indians as rapidly as practicable on the same footing with the other permanent inhabitants of our country.

I do not undertake to apportion the blame for the injustice done to the Poncas. Whether the Executive or Congress or the public is chiefly in fault is not now a question of practical importance. As the Chief Executive at the time when the wrong was consummated, I am deeply sensible that enough of the responsibility for that wrong justly attaches to me to make it my particular duty and earnest desire to do all I can to give to these injured people that measure of redress which is required alike by justice and by humanity.

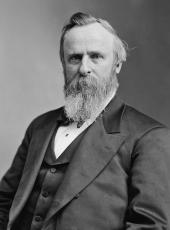

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES

Rutherford B. Hayes, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/204665