To the Senate and House of Representatives:

I have the honor to submit herewith to the two Houses of Congress the report of the commissioners appointed in pursuance of joint resolution approved January 12, 1871.

It will be observed that this report more than sustains all that I have heretofore said in regard to the productiveness and healthfulness of the Republic of San Domingo, of the unanimity of the people for annexation to the United States, and of their peaceable character.

It is due to the public, as it certainly is to myself, that I should here give all the circumstances which first led to the negotiation of a treaty for the annexation of the Republic of San Domingo to the United States.

When I accepted the arduous and responsible position which I now hold, I did not dream of instituting any steps for the acquisition of insular possessions. I believed, however, that our institutions were broad enough to extend over the entire continent as rapidly as other peoples might desire to bring themselves under our protection. I believed further that we should not permit any independent government within the limits of North America to pass from a condition of independence to one of ownership or protection under a European power.

Soon after my inauguration as President I was waited upon by an agent of President Baez with a proposition to annex the Republic of San Domingo to the United States. This gentleman represented the capacity of the island, the desire of the people, and their character and habits about as they have been described by the commissioners whose report accompanies this message. He stated further that, being weak in numbers and poor in purse, they were not capable of developing their great resources; that the people had no incentive to industry on account of lack of protection for their accumulations, and that if not accepted by the United States--with institutions which they loved above those of any other nation--they would be compelled to seek protection elsewhere. To these statements I made no reply and gave no indication of what I thought of the proposition. In the course of time I was waited upon by a second gentleman from San Domingo, who made the same representations, and who was received in like manner.

In view of the facts which had been laid before me, and with an earnest desire to maintain the "Monroe doctrine," I believed that I would be derelict in my duty if I did not take measures to ascertain the exact wish of the Government and inhabitants of the Republic of San Domingo in regard to annexation and communicate the information to the people of the United States. Under the attending circumstances I felt that if I turned a deaf ear to this appeal I might in the future be justly charged with a flagrant neglect of the public interests and an utter disregard of the welfare of a downtrodden race praying for the blessings of a free and strong government and for protection in the enjoyment of the fruits of their own industry.

Those opponents of annexation who have heretofore professed to be preeminently the friends of the rights of man I believed would be my most violent assailants if I neglected so clear a duty. Accordingly, after having appointed a commissioner to visit the island, who declined on account of sickness, I selected a second gentleman, in whose capacity, judgment, and integrity I had, and have yet, the most unbounded confidence.

He visited San Domingo, not to secure or hasten annexation, but, unprejudiced and unbiased, to learn all the facts about the Government, the people, and the resources of that Republic. He went certainly as well prepared to make an unfavorable report as a favorable one, if the facts warranted it. His report fully corroborated the views of previous commissioners, and upon its receipt I felt that a sense of duty and a due regard for our great national interests required me to negotiate a treaty for the acquisition of the Republic of San Domingo.

As soon as it became publicly known that such a treaty had been negotiated, the attention of the country was occupied with allegations calculated to prejudice the merits of the case and with aspersions upon those whose duty had connected them with it. Amid the public excitement thus created the treaty failed to receive the requisite two-thirds vote of the Senate, and was rejected; but whether the action of that body was based wholly upon the merits of the treaty, or might not have been in some degree influenced by such unfounded allegations, could not be known by the people, because the debates of the Senate in secret session are not published.

Under these circumstances I deemed it due to the office which I hold and due to the character of the agents who had been charged with the investigation that such proceedings should be had as would enable the people to know the truth. A commission was therefore constituted, under authority of Congress, consisting of gentlemen selected with special reference to their high character and capacity for the laborious work intrusted to them, who were instructed to visit the spot and report upon the facts. Other eminent citizens were requested to accompany the commission, in order that the people might have the benefit of their views. Students of science and correspondents of the press, without regard to political opinions, were invited to join the expedition, and their numbers were limited only by the capacity of the vessel.

The mere rejection by the Senate of a treaty negotiated by the President only indicates a difference of opinion between two coordinate departments of the Government, without touching the character or wounding the pride of either. But when such rejection takes place simultaneously with charges openly made of corruption on the part of the President or those employed by him the case is different. Indeed, in such case the honor of the nation demands investigation. This has been accomplished by the report of the commissioners herewith transmitted, and which fully vindicates the purity of the motives and action of those who represented the United States in the negotiation.

And now my task is finished, and with it ends all personal solicitude upon the subject. My duty being done, yours begins; and I gladly hand over the whole matter to the judgment of the American people and of their representatives in Congress assembled. The facts will now be spread before the country, and a decision rendered by that tribunal whose convictions so seldom err, and against whose will I have no policy to enforce. My opinion remains unchanged; indeed, it is confirmed by the report that the interests of our country and of San Domingo alike invite the annexation of that Republic.

In view of the difference of opinion upon this subject, I suggest that no action be taken at the present session beyond the printing and general dissemination of the report. Before the next session of Congress the people will have considered the subject and formed an intelligent opinion concerning it, to which opinion, deliberately made up, it will be the duty of every department of the Government to give heed; and no one will more cheerfully conform to it than myself. It is not only the theory of our Constitution that the will of the people, constitutionally expressed, is the supreme law, but I have ever believed that "all men are wiser than any one man;" and if the people, upon a full presentation of the facts, shall decide that the annexation of the Republic is not desirable, every department of the Government ought to acquiesce in that decision.

In again submitting to Congress a subject upon which public sentiment has been divided, and which has been made the occasion of acrimonious debates in Congress, as well as of unjust aspersions elsewhere, I may, I trust, be indulged in a single remark.

No man could hope to perform duties so delicate and responsible as pertain to the Presidential office without sometimes incurring the hostility of those who deem their opinions and wishes treated with insufficient consideration; and he who undertakes to conduct the affairs of a great government as a faithful public servant, if sustained by the approval of his own conscience, may rely with confidence upon the candor and intelligence of a free people whose best interests he has striven to subserve, and can bear with patience the censure of disappointed men.

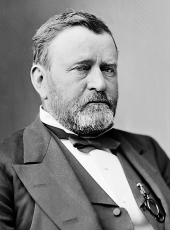

U. S. GRANT.

Ulysses S. Grant, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/204296