Gentlemen of the Senate and House of Representatives.

In my annual message at the commencement of your present session I adverted to the opposition to the revenue laws in a particular quarter of the United States, which threatened not merely to thwart their execution, but to endanger the integrity of the Union; and although I then expressed my reliance that it might be overcome by the prudence of the officers of the United States and the patriotism of the people, I stated that should the emergency arise rendering the execution of the existing laws impracticable from any cause whatever prompt notice should be given to Congress, with the suggestion of such views and measures as might be necessary to meet it.

Events which have occurred in the quarter then alluded to, or which have come to my knowledge subsequently, present this emergency.

Since the date of my last annual message I have had officially transmitted to me by the governor of South Carolina, which I now communicate to Congress, a copy of the ordinance passed by the convention which assembled at Columbia, in the State of South Carolina, in November last, declaring certain acts of Congress therein mentioned within the limits of that State to be absolutely null and void, and making it the duty of the legislature to pass such laws as would be necessary to carry the same into effect from and after the 1st February next.

The consequences to which this extraordinary defiance of the just authority of the Government might too surely lead were clearly foreseen, and it was impossible for me to hesitate as to my own duty in such an emergency.

The ordinance had been passed, however, without any certain knowledge of the recommendation which, from a view of the interests of the nation at large, the Executive had determined to submit to Congress, and a hope was indulged that by frankly explaining his sentiments and the nature of those duties which the crisis would devolve upon him the authorities of South Carolina might be induced to retrace their steps. In this hope I determined to issue my proclamation of the 10th of December last, a copy of which I now lay before Congress.

I regret to inform you that these reasonable expectations have not been realized, and that the several acts of the legislature of South Carolina which I now lay before you, and which have all and each of them finally passed after a knowledge of the desire of the Administration to modify the laws complained of, are too well calculated both in their positive enactments and in the spirit of opposition which they obviously encourage wholly to obstruct the collection of the revenue within the limits of that State.

Up to this period neither the recommendation of the Executive in regard to our financial policy and impost system, nor the disposition manifested by Congress promptly to act upon that subject, nor the unequivocal expression of the public will in all parts of the Union appears to have produced any relaxation in the measures of opposition adopted by the State of South Carolina; nor is there any reason to hope that the ordinance and laws will be abandoned.

I have no knowledge that an attempt has been made, or that it is in contemplation, to reassemble either the convention or the legislature, and it will be perceived that the interval before the 1st of February is too short to admit of the preliminary steps necessary for that purpose. It appears, moreover, that the State authorities are actively organizing their military resources, and providing the means and giving the most solemn assurances of protection and support to all who shall enlist in opposition to the revenue laws.

A recent proclamation of the present governor of South Carolina has openly defied the authority of the Executive of the Union, and general orders from the headquarters of the State announced his determination to accept the services of volunteers and his belief that should their country need their services they will be found at the post of honor and duty, ready to lay down their lives in her defense. Under these orders the forces referred to are directed to "hold themselves in readiness to take the field at a moment's warning," and in the city of Charleston, within a collection district, and a port of entry, a rendezvous has been opened for the purpose of enlisting men for the magazine and municipal guard. Thus South Carolina presents herself in the attitude of hostile preparation, and ready even for military violence if need be to enforce her laws for preventing the collection of the duties within her limits.

Proceedings thus announced and matured must be distinguished from menaces of unlawful resistance by irregular bodies of people, who, acting under temporary delusion, may be restrained by reflection and the influence of public opinion from the commission of actual outrage. In the present instance aggression may be regarded as committed when it is officially authorized and the means of enforcing it fully provided.

Under these circumstances there can be no doubt that it is the determination of the authorities of South Carolina fully to carry into effect their ordinance and laws after the 1st of February. It therefore becomes my duty to bring the subject to the serious consideration of Congress, in order that such measures as they in their wisdom may deem fit shall be seasonably provided, and that it may be thereby understood that while the Government is disposed to remove all just cause of complaint as far as may be practicable consistently with a proper regard to the interests of the community at large, it is nevertheless determined that the supremacy of the laws shall be maintained.

In making this communication it appears to me to be proper not only that I should lay before you the acts and proceedings of South Carolina, but that I should also fully acquaint you with those steps which I have already caused to be taken for the due collection of the revenue, and with my views of the subject generally, that the suggestions which the Constitution requires me to make in regard to your future legislation may be better understood.

This subject having early attracted the anxious attention of the Executive, as soon as it was probable that the authorities of South Carolina seriously meditated resistance to the faithful execution of the revenue laws it was deemed advisable that the Secretary of the Treasury should particularly instruct the officers of the United States in that part of the Union as to the nature of the duties prescribed by the existing laws.

Instructions were accordingly issued on the 6th of November to the collectors in that State, pointing out their respective duties and enjoining upon each a firm and vigilant but discreet performance of them in the emergency then apprehended.

I herewith transmit copies of these instructions and of the letter addressed to the district attorney, requesting his cooperation. These instructions were dictated in the hope that as the opposition to the laws by the anomalous proceeding of nullification was represented to be of a pacific nature, to be pursued substantially according to the forms of the Constitution and without resorting in any event to force or violence, the measures of its advocates would be taken in conformity with that profession, and on such supposition the means afforded by the existing laws would have been adequate to meet any emergency likely to arise.

It was, however, not possible altogether to suppress apprehension of the excesses to which the excitement prevailing in that quarter might lead, but it certainly was not foreseen that the meditated obstruction to the laws would so soon openly assume its present character.

Subsequently to the date of those instructions, however, the ordinance of the convention was passed, which, if complied with by the people of the State, must effectually render inoperative the present revenue laws within her limits.

That ordinance declares and ordains--

That the several acts and parts of acts of the Congress of the United States purporting to be laws for the imposing of duties and imposts on the importation of foreign commodities, and now having operation and effect within the United States, and more especially "An act in alteration of the several acts imposing duties on imports," approved on the 19th of May, 1828, and also an act entitled "An act to alter and amend the several acts imposing duties on imports," approved on the 14th July, 1832, are unauthorized by the Constitution of the United States, and violate the true intent and meaning thereof, and are null and void and no law, nor binding upon the State of South Carolina, its officers and citizens; and all promises, contracts, and obligations made or entered into, or to be made or entered into, with purpose to secure the duties imposed by the said acts, and all judicial proceedings which shall be hereafter had in affirmance thereof, are and shall be held utterly null and void.

It also ordains--

That it shall not be lawful for any of the constituted authorities, whether of the State of South Carolina or of the United States, to enforce the payment of duties imposed by the said acts within the limits of the State, but that it shall be the duty of the legislature to adopt such measures and pass such acts as may be necessary to give full effect to this ordinance and to prevent the enforcement and arrest the operation of the said acts and parts of acts of the Congress of the United States within the limits of the State from and after the 1st of February next; and it shall be the duty of all other constituted authorities and of all other persons residing or being within the limits of the State, and they are hereby required and enjoined, to obey and give effect to this ordinance and such acts and measures of the legislature as may be passed or adopted in obedience thereto.

It further ordains--

That in no case of law or equity decided in the courts of the State wherein shall be drawn in question the authority of this ordinance, or the validity of such act or acts of the legislature as may be passed for the purpose of giving effect thereto, or the validity of the aforesaid acts of Congress imposing duties, shall any appeal be taken or allowed to the Supreme Court of the United States, nor shall any copy of the record be permitted or allowed for that purpose; and the person or persons attempting to take such appeal may be dealt with as for a contempt of court.

It likewise ordains--

That all persons holding any office of honor, profit, or trust, civil or military, under the State shall, within such time and in such manner as the legislature shall prescribe, take an oath well and truly to obey, execute, and enforce this ordinance and such act or acts of the legislature as may be passed in pursuance thereof, according to the true intent and meaning of the same; and on the neglect or omission of any such person or persons so to do his or their office or offices shall be forthwith vacated, and shall be filled up as if such person or persons were dead or had resigned. And no person hereafter elected to any office of honor, profit, or trust, civil or military, shall, until the legislature shall otherwise provide and direct, enter on the execution of his office or be in any respect competent to discharge the duties thereof until he shall in like manner have taken a similar oath; and no juror shall be empaneled in any of the courts of the State in any cause in which shall be in question this ordinance or any act of the legislature passed in pursuance thereof, unless he shall first, in addition to the usual oath, have taken an oath that he will well and truly obey, execute, and enforce this ordinance and such act or acts of the legislature as may be passed to carry the same into operation and effect, according to the true intent and meaning thereof.

The ordinance concludes:

And we, the people of South Carolina, to the end that it may be fully understood by the Government of the United States and the people of the co-States that we are determined to maintain this ordinance and declaration at every hazard, do further declare that we will not submit to the application of force on the part of the Federal Government to reduce this State to obedience, but that we will consider the passage by Congress of any act authorizing the employment of a military or naval force against the State of South Carolina, her constituted authorities or citizens, or any act abolishing or closing the ports of this State, or any of them, or otherwise obstructing the free ingress and egress of vessels to and from the said ports, or any other act on the part of the Federal Government to coerce the State, shut up her ports, destroy or harass her commerce, or to enforce the acts hereby declared to be null and void, otherwise than through the civil tribunals of the country, as inconsistent with the longer continuance of South Carolina in the Union; and that the people of this State will thenceforth hold themselves absolved from all further obligation to maintain or preserve their political connection with the people of the other States, and will forthwith proceed to organize a separate government and to do all other acts and things which sovereign and independent states may of right do.

This solemn denunciation of the laws and authority of the United States has been followed up by a series of acts on the part of the authorities of that State which manifest a determination to render inevitable a resort to those measures of self-defense which the paramount duty of the Federal Government requires, but upon the adoption of which that State will proceed to execute the purpose it has avowed in this ordinance of withdrawing from the Union.

On the 27th of November the legislature assembled at Columbia, and on their meeting the governor laid before them the ordinance of the convention. In his message on that occasion he acquaints them that "this ordinance has thus become a part of the fundamental law of South Carolina;" that "the die has been at last cast, and South Carolina has at length appealed to her ulterior sovereignty as a member of this Confederacy and has planted herself on her reserved rights. The rightful exercise of this power is not a question which we shall any longer argue. It is sufficient that she has willed it, and that the act is done; nor is its strict compatibility with our constitutional obligation to all laws passed by the General Government within the authorized grants of power to be drawn in question when this interposition is exerted in a case in which the compact has been palpably, deliberately, and dangerously violated. That it brings up a conjuncture of deep and momentous interest is neither to be concealed nor denied. This crisis presents a class of duties which is referable to yourselves. You have been commanded by the people in their highest sovereignty to take care that within the limits of this State their will shall be obeyed." "The measure of legislation," he says, "which you have to employ at this crisis is the precise amount of such enactments as may be necessary to render it utterly impossible to collect within our limits the duties imposed by the protective tariffs thus nullified."

He proceeds:

That you should arm every citizen with a civil process by which he may claim, if he pleases, a restitution of his goods seized under the existing imposts on his giving security to abide the issue of a suit at law, and at the same time define what shall constitute treason against the State, and by a bill of pains and penalties compel obedience and punish disobedience to your own laws, are points too obvious to require any discussion. In one word, you must survey the whole ground. You must look to and provide for all possible contingencies. In your own limits your own courts of judicature must not only be supreme, but you must look to the ultimate issue of any conflict of jurisdiction and power between them and the courts of the United States.

The governor also asks for power to grant clearances, in violation of the laws of the Union; and to prepare for the alternative which must happen unless the United States shall passively surrender their authority, and the Executive, disregarding his oath, refrain from executing the laws of the Union, he recommends a thorough revision of the militia system, and that the governor "be authorized to accept for the defense of Charleston and its dependencies the services of 2,000 volunteers, either by companies or files," and that they be formed into a legionary brigade consisting of infantry, riflemen, cavalry, field and heavy artillery, and that they be "armed and equipped from the public arsenals completely for the field, and that appropriations be made for supplying all deficiencies in our munitions of war." In addition to these volunteer drafts, he recommends that the governor be authorized "to accept the services of 10,000 volunteers from the other divisions of the State, to be organized and arranged in regiments and brigades, the officers to be selected by the commander in chief, and that this whole force be called the State guard. "

A request has been regularly made of the secretary of state of South Carolina for authentic copies of the acts which have been passed for the purpose of enforcing the ordinance, but up to the date of the latest advices that request had not been complied with, and on the present occasion, therefore, reference can only be made to those acts as published in the newspapers of the State.

The acts to which it is deemed proper to invite the particular attention of Congress are:

First. "An act to carry into effect, in part, an ordinance to nullify certain acts of the Congress of the United States purporting to be laws laying duties on the importation of foreign commodities," passed in convention of this State, at Columbia, on the 24th November, 1832.

This act provides that any goods seized or detained under pretense of securing the duties, or for the nonpayment of duties, or under any process, order, or decree, or other pretext contrary to the intent and meaning of the ordinance may be recovered by the owner or consignee by "an act of replevin;" that in case of refusing to deliver them, or removing them so that the replevin can not be executed, the sheriff may seize the personal estate of the offender to double the amount of the goods, and if any attempt shall be made to retake or seize them it is the duty of the sheriff to recapture them; and that any person who shall disobey the process or remove the goods, or anyone who shall attempt to retake or seize the goods under pretense of securing the duties, or for nonpayment of duties, or under any process or decree contrary to the intent of the ordinance, shall be fined and imprisoned, besides being liable for any other offense involved in the act.

It also provides that any person arrested or imprisoned on any judgment or decree obtained in any Federal court for duties shall be entitled to the benefit secured by the habeas corpus act of the State in cases of unlawful arrest, and may maintain an action for damages, and that if any estate shall be sold under such judgment or decree the sale shall be held illegal. It also provides that any jailer who receives a person committed on any process or other judicial proceedings to enforce the payment of duties, and anyone who hires his house as a jail to receive such persons, shall be fined and imprisoned. And, finally, it provides that persons paying duties may recover them back with interest.

The next is called "An act to provide for the security and protection of the people of the State of South Carolina."

This act provides that if the Government of the United States or any officer thereof shall, by the employment of naval or military force, attempt to coerce the State of South Carolina into submission to the acts of Congress declared by the ordinance null and void, or to resist the enforcement of the ordinance or of the laws passed in pursuance thereof, or in case of any armed or forcible resistance thereto, the governor is authorized to resist the same and to order into service the whole or so much of the military force of the State as he may deem necessary; and that in case of any overt act of coercion or intention to commit the same, manifested by an unusual assemblage of naval or military forces in or near the State, or the occurrence of any circumstances indicating that armed force is about to be employed against the State or in resistance to its laws, the governor is authorized to accept the services of such volunteers and call into service such portions of the militia as may be required to meet the emergency.

The act also provides for accepting the service of the volunteers and organizing the militia, embracing all free white males between the ages of 16 and 60, and for the purchase of arms, ordnance, and ammunition. It also declares that the power conferred on the governor shall be applicable to all cases of insurrection or invasion, or imminent danger thereof, and to cases where the laws of the State shall be opposed and the execution thereof forcibly resisted by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the power vested in the sheriffs and other civil officers, and declares it to be the duty of the governor in every such case to call forth such portions of the militia and volunteers as may be necessary promptly to suppress such combinations and cause the laws of the State to be executed.

No. 9 is "An act concerning the oath required by the ordinance passed in convention at Columbia on the 24th of November, 1832."

This act prescribes the form of the oath, which is, to obey and execute the ordinance and all acts passed by the legislature in pursuance thereof, and directs the time and manner of taking it by the officers of the State civil, judiciary, and military.

It is believed that other acts have been passed embracing provisions for enforcing the ordinance, but I have not yet been able to procure them.

I transmit, however, a copy of Governor Hamilton's message to the legislature of South Carolina; of Governor Hayne's inaugural address to the same body, as also of his proclamation, and a general order of the governor and commander in chief, dated the 20th of December, giving public notice that the services of volunteers will be accepted under the act already referred to.

If these measures can not be defeated and overcome by the power conferred by the Constitution on the Federal Government, the Constitution must be considered as incompetent to its own defense, the supremacy of the laws is at an end, and the rights and liberties of the citizens can no longer receive protection from the Government of the Union. They not only abrogate the acts of Congress commonly called the tariff acts of 1828 and 1832, but they prostrate and sweep away at once and without exception every act and every part of every act imposing any amount whatever of duty on any foreign merchandise, and virtually every existing act which has ever been passed authorizing the collection of the revenue, including the act of 1816, and also the collection law of 1799, the constitutionality of which has never been questioned. It is not only those duties which are charged to have been imposed for the protection of manufactures that are thereby repealed, but all others, though laid for the purpose of revenue merely, and upon articles in no degree suspected of being objects of protection. The whole revenue system of the United States in South Carolina is obstructed and overthrown, and the Government is absolutely prohibited from collecting any part of the public revenue within the limits of that State. Henceforth, not only the citizens of South Carolina and of the United States, but the subjects of foreign states may import any description or quantity of merchandise into the ports of South Carolina without the payment of any duty whatsoever. That State is thus relieved from the payment of any part of the public burthens, and duties and imposts are not only rendered not uniform throughout the United States, but a direct and ruinous preference is given to the ports of that State over those of all the other States of the Union, in manifest violation of the positive provisions of the Constitution.

In point of duration, also, those aggressions upon the authority of Congress which by the ordinance are made part of the fundamental law of South Carolina are absolute, indefinite, and without limitation. They neither prescribe the period when they shall cease nor indicate any conditions upon which those who have thus undertaken to arrest the operation of the laws are to retrace their steps and rescind their measures. They offer to the United States no alternative but unconditional submission. If the scope of the ordinance is to be received as the scale of concession, their demands can be satisfied only by a repeal of the whole system of revenue laws and by abstaining from the collection of any duties and imposts whatsoever.

It is true that in the address to the people of the United States by the convention of South Carolina, after announcing "the fixed and final determination of the State in relation to the protecting system," they say "that it remains for us to submit a plan of taxation in which we would be willing to acquiesce in a liberal spirit of concession, provided we are met in due time and in a becoming spirit by the States interested in manufactures." In the opinion of the convention, an equitable plan would be that "the whole list of protected articles should be imported free of all duty, and that the revenue derived from import duties should be raised exclusively from the unprotected articles, or that whenever a duty is imposed upon protected articles imported an excise duty of the same rate shall be imposed upon all similar articles manufactured in the United States."

The address proceeds to state, however, that "they are willing to make a large offering to preserve the Union, and, with a distinct declaration that it is a concession on our part, we will consent that the same rate of duty may be imposed upon the protected articles that shall be imposed upon the unprotected, provided that no more revenue be raised than is necessary to meet the demands of the Government for constitutional purposes, and provided also that a duty substantially uniform be imposed upon all foreign imports."

It is also true that in his message to the legislature, when urging the necessity of providing "means of securing their safety by ample resources for repelling force by force," the governor of South Carolina observes that he "can not but think that on a calm and dispassionate review by Congress and the functionaries of the General Government of the true merits of this controversy the arbitration by a call of a convention of all the States, which we sincerely and anxiously seek and desire, will be accorded to us."

From the diversity of terms indicated in these two important documents, taken in connection with the progress of recent events in that quarter, there is too much reason to apprehend, without in any manner doubting the intentions of those public functionaries, that neither the terms proposed in the address of the convention nor those alluded to in the message of the governor would appease the excitement which has led to the present excesses. It is obvious, however, that should the latter be insisted on they present an alternative which the General Government of itself can by no possibility grant, since by an express provision of the Constitution Congress can call a convention for the purpose of proposing amendments only "on the application of the legislatures of two-thirds of the States." And it is not perceived that the terms presented in the address are more practicable than those referred to in the message.

It will not escape attention that the conditions on which it is said in the address of the convention they "would be willing to acquiesce" form no part of the ordinance. While this ordinance bears all the solemnity of a fundamental law, is to be authoritative upon all within the limits of South Carolina, and is absolute and unconditional in its terms, the address conveys only the sentiments of the convention, in no binding or practical form; one is the act of the State, the other only the expression of the opinions of the members of the convention. To limit the effect of that solemn act by any terms or conditions whatever, they should have been embodied in it, and made of import no less authoritative than the act itself. By the positive enactments of the ordinance the execution of the laws of the Union is absolutely prohibited, and the address offers no other prospect of their being again restored, even in the modified form proposed, than what depends upon the improbable contingency that amid changing events and increasing excitement the sentiments of the present members of the convention and of their successors will remain the same.

It is to be regretted, however, that these conditions, even if they had been offered in the same binding form, are so undefined, depend upon so many contingencies, and are so directly opposed to the known opinions and interests of the great body of the American people as to be almost hopeless of attainment. The majority of the States and of the people will certainly not consent that the protecting duties shall be wholly abrogated, never to be reenacted at any future time or in any possible contingency. As little practicable is it to provide that "the same rate of duty shall be imposed upon the protected articles that shall be imposed upon the unprotected," which, moreover, would be severely oppressive to the poor, and in time of war would add greatly to its rigors. And though there can be no objection to the principle, properly understood, that no more revenue shall be raised than is necessary for the constitutional purposes of the Government, which principle has been already recommended by the Executive as the true basis of taxation, yet it is very certain that South Carolina alone can not be permitted to decide what these constitutional purposes are.

The period which constitutes the due time in which the terms proposed in the address are to be accepted would seem to present scarcely less difficulty than the terms themselves. Though the revenue laws are already declared to be void in South Carolina, as well as the bonds taken under them and the judicial proceedings for carrying them into effect, yet as the full action and operation of the ordinance are to be suspended until the 1st of February the interval may be assumed as the time within which it is expected that the most complicated portion of the national legislation, a system of long standing and affecting great interests in the community, is to be rescinded and abolished. If this be required, it is clear that a compliance is impossible.

In the uncertainty, then, that exists as to the duration of the ordinance and of the enactments for enforcing it, it becomes imperiously the duty of the Executive of the United States, acting with a proper regard to all the great interests committed to his care, to treat those acts as absolute and unlimited. They are so as far as his agency is concerned. He can not either embrace or lead to the performance of the conditions. He has already discharged the only part in his power by the recommendation in his annual message. The rest is with Congress and the people, and until they have acted his duty will require him to look to the existing state of things and act under them according to his high obligations.

By these various proceedings, therefore, the State of South Carolina has forced the General Government, unavoidably, to decide the new and dangerous alternative of permitting a State to obstruct the execution of the laws within its limits or seeing it attempt to execute a threat of withdrawing from the Union. That portion of the people at present exercising the authority of the State solemnly assert their right to do either and as solemnly announce their determination to do one or the other.

In my opinion, both purposes are to be regarded as revolutionary in their character and tendency, and subversive of the supremacy of the laws and of the integrity of the Union. The result of each is the same, since a State in which, by an usurpation of power, the constitutional authority of the Federal Government is openly defied and set aside wants only the form to be independent of the Union.

The right of the people of a single State to absolve themselves at will and without the consent of the other States from their most solemn obligations, and hazard the liberties and happiness of the millions composing this Union, can not be acknowledged. Such authority is believed to be utterly repugnant both to the principles upon which the General Government is constituted and to the objects which it is expressly formed to attain.

Against all acts which may be alleged to transcend the constitutional power of the Government, or which may be inconvenient or oppressive in their operation, the Constitution itself has prescribed the modes of redress. It is the acknowledged attribute of free institutions that under them the empire of reason and law is substituted for the power of the sword. To no other source can appeals for supposed wrongs be made consistently with the obligations of South Carolina; to no other can such appeals be made with safety at any time; and to their decisions, when constitutionally pronounced, it becomes the duty no less of the public authorities than of the people in every case to yield a patriotic submission.

That a State or any other great portion of the people, suffering under long and intolerable oppression and having tried all constitutional remedies without the hope of redress, may have a natural right, when their happiness can be no otherwise secured, and when they can do so without greater injury to others, to absolve themselves from their obligations to the Government and appeal to the last resort, needs not on the present occasion be denied.

The existence of this right, however, must depend upon the causes which may justify its exercise. It is the ultima ratio, which presupposes that the proper appeals to all other means of redress have been made in good faith, and which can never be rightfully resorted to unless it be unavoidable. It is not the right of the State, but of the individual, and of all the individuals in the State. It is the right of mankind generally to secure by all means in their power the blessings of liberty and happiness; but when for these purposes any body of men have voluntarily associated themselves under a particular form of government, no portion of them can dissolve the association without acknowledging the correlative right in the remainder to decide whether that dissolution can be permitted consistently with the general happiness. In this view it is a right dependent upon the power to enforce it. Such a right, though may be admitted to preexist and can not be wholly surrendered, is necessarily subjected to limitations in all free governments, and in compacts of all kinds freely and voluntarily entered into, and in which the interest and welfare of the individual become identified with those of the community of which he is a member. In compacts between individuals, however deeply they may affect their relations, these principles are acknowledged to create a sacred obligation; and in compacts of civil government, involving the liberties and happiness of millions of mankind, the obligation can not be less.

Without adverting to the particular theories to which the federal compact has given rise, both as to its formation and the parties to it, and without inquiring whether it be merely federal or social or national, it is sufficient that it must be admitted to be a compact and to possess the obligations incident to a compact; to be "a compact by which power is created on the one hand and obedience exacted on the other; a compact freely, voluntarily, and solemnly entered into by the several States and ratified by the people thereof, respectively; a compact by which the several States and the people thereof, respectively, have bound themselves to each other and to the Federal Government, and by which the Federal Government is bound to the several States and to every citizen of the United States." To this compact, in whatever mode it may have been done, the people of South Carolina have freely and voluntarily given their assent, and to the whole and every part of it they are, upon every principle of good faith, inviolably bound. Under this obligation they are bound and should be required to contribute their portion of the public expense, and to submit to all laws made by the common consent, in pursuance of the Constitution, for the common defense and general welfare, until they can be changed in the mode which the compact has provided for the attainment of those great ends of the Government and of the Union. Nothing less than causes which would justify revolutionary remedy can absolve the people from this obligation, and for nothing less can the Government permit it to be done without violating its own obligations, by which, under the compact, it is bound to the other States and to every citizen of the United States.

These deductions plainly flow from the nature of the federal compact, which is one of limitations, not only upon the powers originally possessed by the parties thereto, but also upon those conferred on the Government and every department thereof. It will be freely conceded that by the principles of our system all power is vested in the people, but to be exercised in the mode and subject to the checks which the people themselves have prescribed. These checks are undoubtedly only different modifications of the same great popular principle which lies at the foundation of the whole, but are not on that account to be less regarded or less obligatory.

Upon the power of Congress, the veto of the Executive and the authority of the judiciary, which is to extend to all cases in law and equity arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States made in pursuance thereof, are the obvious checks, and the sound action of public opinion, with the ultimate power of amendment, are the salutary and only limitation upon the powers of the whole.

However it may be alleged that a violation of the compact by the measures of the Government can affect the obligations of the parties, it can not even be pretended that such violation can be predicated of those measures until all the constitutional remedies shall have been fully tried. If the Federal Government exercise powers not warranted by the Constitution, and immediately affecting individuals, it will scarcely be denied that the proper remedy is a recourse to the judiciary. Such undoubtedly is the remedy for those who deem the acts of Congress laying duties and imposts, and providing for their collection, to be unconstitutional. The whole operation of such laws is upon the individuals importing the merchandise. A State is absolutely prohibited from laying imposts or duties on imports or exports without the consent of Congress, and can not become a party under these laws without importing in her own name or wrongfully interposing her authority against them. By thus interposing, however, she can not rightfully obstruct the operation of the laws upon individuals. For their disobedience to or violation of the laws the ordinary remedies through the judicial tribunals would remain. And in a case where an individual should be prosecuted for any offense against the laws, he could not set up in justification of his act a law of the State, which, being unconstitutional, would therefore be regarded as null and void. The law of a State can not authorize the commission of a crime against the United States or any other act which, according to the supreme law of the Union, would be otherwise unlawful; and it is equally clear that if there be any case in which a State, as such, is affected by the law beyond the scope of judicial power, the remedy consists in appeals to the people, either to effect a change in the representation or to procure relief by an amendment of the Constitution. But the measures of the Government are to be recognized as valid, and consequently supreme, until these remedies shall have been effectually tried, and any attempt to subvert those measures or to render the laws subordinate to State authority, and afterwards to resort to constitutional redress, is worse than evasive. It would not be a proper resistance to "a government of unlimited powers," as has been sometimes pretended, but unlawful opposition to the very limitations on which the harmonious action of the Government and all its parts absolutely depends. South Carolina has appealed to none of these remedies, but in effect has defied them all. While threatening to separate from the Union if any attempt be made to enforce the revenue laws otherwise than through the civil tribunals of the country, she has not only not appealed in her own name to those tribunals which the Constitution has provided for all cases in law or equity arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States, but has endeavored to frustrate their proper action on her citizens by drawing the cognizance of cases under the revenue laws to her own tribunals, specially prepared and fitted for the purpose of enforcing the acts passed by the State to obstruct those laws, and both the judges and jurors of which will be bound by the import of oaths previously taken to treat the Constitution and laws of the United States in this respect as a nullity. Nor has the State made the proper appeal to public opinion and to the remedy of amendment; for without waiting to learn whether the other States will consent to a convention, or if they do will construe or amend the Constitution to suit her views, she has of her own authority altered the import of that instrument and given immediate effect to the change. In fine, she has set her own will and authority above the laws, has made herself arbiter in her own cause, and has passed at once over all intermediate steps to measures of avowed resistance, which, unless they be submitted to, can be enforced only by the sword.

In deciding upon the course which a high sense of duty to all the people of the United States imposes upon the authorities of the Union in this emergency, it can not be overlooked that there is no sufficient cause for the acts of South Carolina, or for her thus placing in jeopardy the happiness of so many millions of people. Misrule and oppression, to warrant the disruption of the free institutions of the Union of these States, should be great and lasting, defying all other remedy. For causes of minor character the Government could not submit to such a catastrophe without a violation of its most sacred obligations to the other States of the Union who have submitted their destiny to its hands.

There is in the present instance no such cause, either in the degree of misrule or oppression complained of or in the hopelessness of redress by constitutional means. The long sanction they have received from the proper authorities and from the people, not less than the unexampled growth and increasing prosperity of so many millions of freemen, attest that no such oppression as would justify, or even palliate, such a resort can be justly imputed either to the present policy or past measures of the Federal Government.

The same mode of collecting duties, and for the same general objects, which began with the foundation of the Government, and which has conducted the country through its subsequent steps to its present enviable condition of happiness and renown, has not been changed. Taxation and representation, the great principle of the American Revolution, have continually gone hand in hand, and at all times and in every instance no tax of any kind has been imposed without their participation, and, in some instances which have been complained of, with the express assent of a part of the representatives of South Carolina in the councils of the Government. Up to the present period no revenue has been raised beyond the necessary wants of the country and the authorized expenditures of the Government; and as soon as the burthen of the public debt is removed those charged with the administration have promptly recommended a corresponding reduction of revenue.

That this system thus pursued has resulted in no such oppression upon South Carolina needs no other proof than the solemn and official declaration of the late chief magistrate of that State in his address to the legislature. In that he says that--

The occurrences of the past year, in connection with our domestic concerns, are to be reviewed with a sentiment of fervent gratitude to the Great Disposer of Human Events; that tributes of grateful acknowledgment are due for the various and multiplied blessings He has been pleased to bestow on our people; that abundant harvests in every quarter of the State have crowned the exertions of agricultural labor; that health almost beyond former precedent has blessed our homes, and that there is not less reason for thankfulness in surveying our social condition.

It would indeed be difficult to imagine oppression where in the social condition of a people there was equal cause of thankfulness as for abundant harvests and varied and multiplied blessings with which a kind providence had favored them.

Independently of these considerations, it will not escape observation that South Carolina still claims to be a component part of the Union, to participate in the national councils and to share in the public benefits without contributing to the public burdens, thus asserting the dangerous anomaly of continuing in an association without acknowledging any other obligation to its laws than what depends upon her own will.

In this posture of affairs the duty of the Government seems to be plain. It inculcates a recognition of that State as a member of the Union and subject to its authority, a vindication of the just power of the Constitution, the preservation of the integrity of the Union, and the execution of the laws by all constitutional means.

The Constitution, which his oath of office obliges him to support, declares that the Executive "shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed," and in providing that he shall from time to time give to Congress information of the state of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient, imposes the additional obligation of recommending to Congress such more efficient provision for executing the laws as may from time to time be found requisite.

The same instrument confers on Congress the power not merely to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare, but "to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into effect the foregoing powers and all other powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States or in any department or officer thereof," and also to provide for calling forth the militia for executing the laws of the Union. In all cases similar to the present the duties of the Government become the measure of its powers, and whenever it fails to exercise a power necessary and proper to the discharge of the duty prescribed by the Constitution it violates the public trusts not less than it would in transcending its proper limits. To refrain, therefore, from the high and solemn duties thus enjoined, however painful the performance may be, and thereby tacitly permit the rightful authority of the Government to be contemned and its laws obstructed by a single State, would neither comport with its own safety nor the rights of the great body of the American people.

It being thus shown to be the duty of the Executive to execute the laws by all constitutional means, it remains to consider the extent of those already at his disposal and what it may be proper further to provide.

In the instructions of the Secretary of the Treasury to the collectors in South Carolina the provisions and regulations made by the act of 1799, and also the fines, penalties, and forfeitures for their enforcement, are particularly detailed and explained. It may be well apprehended, however, that these provisions may prove inadequate to meet such an open, powerful, organized opposition as is to be commenced after the 1st of February next.

Subsequently to the date of these instructions and to the passage of the ordinance, information has been received from sources entitled to be relied on that owing to the popular excitement in the State and the effect of the ordinance declaring the execution of the revenue laws unlawful a sufficient number of persons in whom confidence might be placed could not be induced to accept the office of inspector to oppose with any probability of success the force which will no doubt be used when an attempt is made to remove vessels and their cargoes from the custody of the officers of the customs, and, indeed, that it would be impracticable for the collector, with the aid of any number of inspectors whom he may be authorized to employ, to preserve the custody against such an attempt.

The removal of the custom-house from Charleston to Castle Pinckney was deemed a measure of necessary precaution, and though the authority to give that direction is not questioned, it is nevertheless apparent that a similar precaution can not be observed in regard to the ports of Georgetown and Beaufort, each of which under the present laws remains a port of entry and exposed to the obstructions meditated in that quarter.

In considering the best means of avoiding or of preventing the apprehended obstruction to the collection of the revenue, and the consequences which may ensue, it would appear to be proper and necessary to enable the officers of the customs to preserve the custody of vessels and their cargoes, which by the existing laws they are required to take, until the duties to which they are liable shall be paid or secured. The mode by which it is contemplated to deprive them of that custody is the process of replevin and that of capias in withernam , in the nature of a distress from the State tribunals organized by the ordinance.

Against the proceeding in the nature of a distress it is not perceived that the collector can interpose any resistance whatever, and against the process of replevin authorized by the law of the State he, having no common-law power, can only oppose such inspectors as he is by statute authorized and may find it practicable to employ, and these, from the information already adverted to, are shown to be wholly inadequate.

The respect which that process deserves must therefore be considered.

If the authorities of South Carolina had not obstructed the legitimate action of the courts of the United States, or if they had permitted the State tribunals to administer the law according to their oath under the Constitution and the regulations of the laws of the Union, the General Government might have been content to look to them for maintaining the custody and to encounter the other inconveniences arising out of the recent proceedings. Even in that case, however, the process of replevin from the courts of the State would be irregular and unauthorized. It has been decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that the courts of the United States have exclusive jurisdiction of all seizures made on land or water for a breach of the laws of the United States, and any intervention of a State authority which, by taking the thing seized out of the hands of the United States officer, might obstruct the exercise of this jurisdiction is unlawful; that in such case the court of the United States having cognizance of the seizure may enforce a redelivery of the thing by attachment or other summary process; that the question under such a seizure whether a forfeiture has been actually incurred belongs exclusively to the courts of the United States, and it depends on the final decree whether the seizure is to be deemed rightful or tortuous; and that not until the seizure be finally judged wrongful and without probable cause by the courts of the United States can the party proceed at common law for damages in the State courts.

But by making it "unlawful for any of the constituted authorities, whether of the United States or of the State, to enforce the laws for the payment of duties, and declaring that all judicial proceedings which shall be hereafter had in affirmance of the contracts made with purpose to secure the duties imposed by the said acts are and shall be held utterly null and void," she has in effect abrogated the judicial tribunals within her limits in this respect, has virtually denied the United States access to the courts established by their own laws, and declared it unlawful for the judges to discharge those duties which they are sworn to perform. In lieu of these she has substituted those State tribunals already adverted to, the judges whereof are not merely forbidden to allow an appeal or permit a copy of their record, but are previously sworn to disregard the laws of the Union and enforce those only of South Carolina, and thus deprived of the function essential to the judicial character of inquiring into the validity of the law and the right of the matter, become merely ministerial instruments in aid of the concerted obstruction of the laws of the Union.

Neither the process nor authority of these tribunals thus constituted can be respected consistently with the supremacy of the laws or the rights and security of the citizen. If they be submitted to, the protection due from the Government to its officers and citizens is withheld, and there is at once an end not only to the laws, but to the Union itself.

Against such a force as the sheriff may, and which by the replevin law of South Carolina it is his duty to exercise, it can not be expected that a collector can retain his custody with the aid of the inspectors. In such case, it is true, it would be competent to institute suits in the United States courts against those engaged in the unlawful proceeding, or the property might be seized for a violation of the revenue laws, and, being libeled in the proper courts, an order might be made for its redelivery, which would be committed to the marshal for execution. But in that case the fourth section of the act, in broad and unqualified terms, makes it the duty of the sheriff "to prevent such recapture or seizure, or to redeliver the goods, as the case may be," "even under any process, order, or decrees, or other pretext contrary to the true intent and meaning of the ordinance aforesaid." It is thus made the duty of the sheriff to oppose the process of the courts of the United States, and for that purpose, if need be, to employ the whole power of the county. And the act expressly reserves to him all power which, independently of its provisions, he could have used. In this reservation it obviously contemplates a resort to other means than those particularly mentioned.

It is not to be disguised that the power which it is thus enjoined upon the sheriff to employ is nothing less than the posse comitatus in all the rigor of the ancient common law. This power, though it may be used against unlawful resistance to judicial process, is in its character forcible, and analogous to that conferred upon the marshals by the act of 1795. It is, in fact, the embodying of the whole mass of the population, under the command of a single individual, to accomplish by their forcible aid what could not be effected peaceably and by the ordinary means. It may properly be said to be a relic of those ages in which the laws could be defended rather by physical than moral force, and in its origin was conferred upon the sheriffs of England to enable them to defend their county against any of the King's enemies when they came into the land, as well as for the purpose of executing process. In early and less civilized times it was intended to include "the aid and attendance of all knights and others who were bound to have harness." It includes the right of going with arms and military equipment, and embraces larger classes and greater masses of population than can be compelled by the laws of most of the States to perform militia duty. If the principles of the common law are recognized in South Carolina (and from this act it would seem they are), the power of summoning the posse comitatus will compel, under the penalty of fine and imprisonment, every man over the age of 15, and able to travel, to turn out at the call of the sheriff, and with such weapons as may be necessary; and it my justify beating, and even killing, such as may resist. The use of the posse comitatus is therefore a direct application of force, and can not be otherwise regarded than as the employment of the whole militia force of the county, and in an equally efficient form under a different name. No proceeding which resorts to this power to the extent contemplated by the act can be properly denominated peaceable.

The act of South Carolina, however, does not rely altogether upon this forcible remedy. For even attempting to resist or disobey, though by the aid only of the ordinary officers of the customs, the process of replevin, the collector and all concerned are subjected to a further proceeding in the nature of a distress of their personal effects, and are, moreover, made guilty of a misdemeanor, and liable to be punished by a fine of not less than $1,000 nor more than $5,000 and to imprisonment not exceeding two years and not less than six months; and for even attempting to execute the order of the court for retaking the property the marshal and all assisting would be guilty of a misdemeanor and liable to a fine of not less than $3,000 nor more than $10,000 and to imprisonment not exceeding two years nor less than one; and in case the goods should be retaken under such process it is made the absolute duty of the sheriff to retake them.

It is not to be supposed that in the face of these penalties, aided by the powerful force of the county, which would doubtless be brought to sustain the State officers, either that the collector would retain the custody in the first instance or that the marshal could summon sufficient aid to retake the property pursuant to the order or other process of the court.

It is, moreover, obvious that in this conflict between the powers of the officers of the United States and of the State (unless the latter be passively submitted to) the destruction to which the property of the officers of the customs would be exposed, the commission of actual violence, and the loss of lives would be scarcely avoidable.

Under these circumstances and the provisions of the acts of South Carolina the execution of the laws is rendered impracticable even through the ordinary judicial tribunals of the United States. There would certainly be fewer difficulties, and less opportunity of actual collision between the officers of the United States and of the State, and the collection of the revenue would be more effectually secured--if, indeed, it can be done in any other way--by placing the custom-house beyond the immediate power of the county.

For this purpose it might be proper to provide that whenever by any unlawful combination or obstruction in any State or in any port it should become impracticable faithfully to collect the duties, the President of the United States should be authorized to alter and abolish such of the districts and ports of entry as should be necessary, and to establish the custom-house at some secure place within some port or harbor of such State; and in such cases it should be the duty of the collector to reside at such place, and to detain all vessels and cargoes until the duties imposed by law should be properly secured or paid in cash, deducting interest; that in such cases it should be unlawful to take the vessel and cargo from the custody of the proper officer of the customs unless by process from the ordinary judicial tribunals of the United States, and that in case of an attempt otherwise to take the property by a force too great to be overcome by the officers of the customs it should be lawful to protect the possession of the officers by the employment of the land and naval forces and militia, under provisions similar to those authorized by the eleventh section of the act of the 9th of January, 1809.

This provision, however, would not shield the officers and citizens of the United States, acting under the laws, from suits and prosecutions in the tribunals of the State which might thereafter be brought against them, nor would it protect their property from the proceeding by distress, and it may well be apprehended that it would be insufficient to insure a proper respect to the process of the constitutional tribunals in prosecutions for offenses against the United States and to protect the authorities of the United States, whether judicial or ministerial, in the performance of their duties. It would, moreover, be inadequate to extend the protection due from the Government to that portion of the people of South Carolina against outrage and oppression of any kind who may manifest their attachment and yield obedience to the laws of the Union.

It may therefore be desirable to revive, with some modifications better adapted to the occasion, the sixth section of the act of the 3d March, 1815, which expired on the 4th March, 1817, by the limitation of that of 27th April, 1816, and to provide that in any case where suit shall be brought against any individual in the courts of the State for any act done under the laws of the United States he should be authorized to remove the said cause by petition into the circuit court of the United States without any copy of the record, and that the court should proceed to hear and determine the same as if it had been originally instituted therein; and that in all cases of injuries to the persons or property of individuals for disobedience to the ordinance and laws of South Carolina in pursuance thereof redress may be sought in the courts of the United States. It may be expedient also, by modifying the resolution of the 3d March, 1791, to authorize the marshals to make the necessary provision for the safe-keeping of prisoners committed under the authority of the United States.

Provisions less than these, consisting as they do for the most part rather of a revival of the policy of former acts called for by the existing emergency than of the introduction of any unusual or rigorous enactments, would not cause the laws of the Union to be properly respected or enforced. It is believed these would prove adequate unless the military forces of the State of South Carolina authorized by the late act of the legislature should be actually embodied and called out in aid of their proceedings and of the provisions of the ordinance generally. Even in that case, however, it is believed that no more will be necessary than a few modifications of its terms to adapt the act of 1795 to the present emergency, as by that act the provisions of the law of 1792 were accommodated to the crisis then existing, and by conferring authority upon the President to give it operation during the session of Congress, and without the ceremony of a proclamation, whenever it shall be officially made known to him by the authority of any State, or by the courts of the United States, that within the limits of such State the laws of the United States will be openly opposed and their execution obstructed by the actual employment of military force, or by any unlawful means whatsoever too great to be otherwise overcome.

In closing this communication, I should do injustice to my own feelings not to express my confident reliance upon the disposition of each department of the Government to perform its duty and to cooperate in all measures necessary in the present emergency.

The crisis undoubtedly invokes the fidelity of the patriot and the sagacity cf the statesman, not more in removing such portion of the public burden as may be necessary than in preserving the good order of society and in the maintenance of well-regulated liberty.

While a forbearing spirit may, and I trust will, be exercised toward the errors of our brethren in a particular quarter, duty to the rest of the Union demands that open and organized resistance to the laws should not be executed with impunity.

The rich inheritance bequeathed by our fathers has devolved upon us the sacred obligation of preserving it by the same virtues which conducted them through the eventful scenes of the Revolution and ultimately crowned their struggle with the noblest model of civil institutions. They bequeathed to us a Government of laws and a Federal Union founded upon the great principle of popular representation. After a successful experiment of forty-four years, at a moment when the Government and the Union are the objects of the hopes of the friends of civil liberty throughout the world, and in the midst of public and individual prosperity unexampled in history, we are called to decide whether these laws possess any force and that Union the means of self-preservation. The decision of this question by an enlightened and patriotic people can not be doubtful. For myself, fellow-citizens, devoutly relying upon that kind Providence which has hitherto watched over our destinies, and actuated by a profound reverence for those institutions I have so much cause to love, and for the American people, whose partiality honored me with their highest trust, I have determined to spare no effort to discharge the duty which in this conjuncture is devolved upon me. That a similar spirit will actuate the representatives of the American people is not to be questioned; and I fervently pray that the Great Ruler of Nations may so guide your deliberations and our joint measures as that they may prove salutary examples not only to the present but to future times, and solemnly proclaim that the Constitution and the laws are supreme and the Union indissoluble.

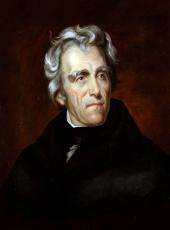

Andrew Jackson, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/200685