To the House of Representatives:

I herewith return without approval House bill No. 2971, entitled "An act granting a pension to Francis Deming."

This claimant entered the service in August, 1861, and was discharged September 15, 1865.

His hospital record shows that during his service he was treated for various temporary ailments, among which rheumatism is not included.

He filed an application for pension in September, 1884, alleging that in August, 1864, he contracted rheumatism, which had resulted in blindness.

On an examination of his case in November, 1884, he stated that his eyesight began to fail in 1882.

There seems to be no testimony showing his condition from the time of his discharge to 1880, a period of fifteen years.

The claim that his present condition of blindness is the result of his army service is not insisted upon as a reason for granting him relief as strongly as his sad and helpless condition. The committee of the House to which this bill was referred, after detailing his situation, close their report with these words: "He served well his country in its dire need; his necessities now appeal for relief."

We have here presented the case of a soldier who did his duty during his army service, and who was discharged in 1865 without any record of having suffered with rheumatism and without any claim of disability arising from the same. He returned to his place as a citizen, and in peaceful pursuits, with chances certainly not impaired by the circumstance that he had served his country, he appears to have held his place in the race of life for fifteen years or more. Then, like many another, he was subjected to loss of sight, one of the saddest afflictions known to human life.

Thereupon, and after nineteen years had elapsed since his discharge from the Army, a pension is claimed for him upon a very shadowy allegation of the incurrence of rheumatism while in the service, coupled with the startling proposition that this rheumatism resulted, just previous to his application, in blindness. Upon medical examination it appeared that his blindness was caused by amaurosis, which is generally accepted as an affection of the optic nerve.

I am satisfied that a fair examination of the facts in this case justifies the statement that the bill under consideration can rest only upon the grounds that aid should be furnished to this ex-soldier because he served in the Army and because he a long time thereafter became blind, disabled, and dependent.

The question is whether we are prepared to adopt this principle and establish this precedent.

None of us are entitled to credit for extreme tenderness and consideration toward those who fought their country's battles. These are sentiments common to all good citizens. They lead to the most benevolent care on the part of the Government and deeds of charity and mercy in private life. The blatant and noisy self-assertion of those who, from motives that may well be suspected, declare themselves above all others friends of the soldier can not discredit nor belittle the calm, steady, and affectionate regard of a grateful nation.

An appropriation has just been passed setting apart $76,000,000 of the public money for distribution as pensions, under laws liberally constructed, with a view of meeting every meritorious case. More than $1,000,000 was added to maintain the Pension Bureau, which is charged with the duty of a fair, just, and liberal apportionment of this fund.

Legislation has been at the present session of Congress perfected considerably increasing the rate of pension in certain cases. Appropriations have also been made of large sums for the support of national homes where sick, disabled, or needy soldiers are cared for, and within a few days a liberal sum has been appropriated for the enlargement and increased accommodation and convenience of these institutions.

All this is no more than should be done.

But with all this, and with the hundreds of special acts which have been passed granting pensions in cases where, for my part, I am willing to confess that sympathy rather than judgment has often led to the discovery of a relation between injury or death and military service, I am constrained by a sense of public duty to interpose against establishing a principle and setting a precedent which must result in unregulated, partial, and unjust gifts of public money under the pretext of indemnifying those who suffered in their means of support as an incident of military service.

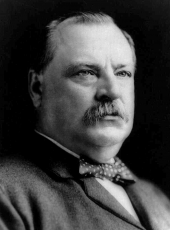

GROVER CLEVELAND

Grover Cleveland, Veto Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/204635