To the Senate of the United States:

I have considered, with such care as the pressure of other duties has permitted, a bill entitled "An act to amend an act entitled 'An act to amend the judiciary act, passed the 24th of September, 1789.'" Not being able to approve all of its provisions, I herewith return it to the Senate, in which House it originated, with a brief statement of my objections.

The first section of the bill meets my approbation, as, for the purpose of protecting the rights of property from the erroneous decision of inferior judicial tribunals, it provides means for obtaining uniformity, by appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States, in cases which have now become very numerous and of much public interest, and in which such remedy is not now allowed. The second section, however, takes away the right of appeal to that court in cases which involve the life and liberty of the citizen. and leaves them exposed to the judgment of numerous interior tribunals. It is apparent that the two sections were conceived in a very, different spirit, and I regret that my objections to one impose upon me the necessity of withholding my sanction from the other.

I can not give my assent to a measure which proposes to deprive any person "restrained of his or her liberty in violation of the Constitution or of any treaty. or law of the United States" from the right of appeal to the highest judicial authority. known to our Government. To "secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity" is one of the declared objects of the Federal Constitution. To assure these, guaranties are provided in the same instrument, as well against "unreasonable searches and seizures" as against the suspensions of "the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus , * * * unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it." It was doubtless to afford the people the means of protecting and enforcing these inestimable privileges that the jurisdiction which this bill proposes to take away was conferred upon the Supreme Court of the nation. The act conferring that jurisdiction was approved on the 5th day of February, 1867, with a full knowledge of the motives that prompted its passage, and because it was believed to be necessary and right. Nothing has since occurred to disprove the wisdom and justness of the measures, and to modify it as now proposed would be to lessen the protection of the citizen from the exercise of arbitrary power and to weaken the safeguards of life and liberty, which can never be made too secure against illegal encroachments.

The bill not only prohibits the adjudication by the Supreme Court of cases in which appeals may hereafter be taken, but interdicts its jurisdiction on appeals which have already been made to that high judicial body. If, therefore, it should become a law, it will by its retroactive operation wrest from the citizen a remedy which he enjoyed at the time of his appeal. It will thus operate most harshly upon those who believe that justice has been denied them in the inferior courts.

The legislation proposed in the second section, it seems to me, is not in harmony with the spirit and intention of the Constitution. It can not fail to affect most injuriously the just equipoise of our system of Government, for it establishes a precedent which, if followed, may eventually sweep away every check on arbitrary and unconstitutional legislation. Thus far during the existence of the Government the Supreme Court of the United States has been viewed by the people as the true expounder of their Constitution, and in the most violent party conflicts its judgments and decrees have always been sought and deferred to with confidence and respect. In public estimation it combines judicial wisdom and impartiality in a greater degree than any other authority known to the Constitution, and any act which may be construed into or mistaken for an attempt to prevent or evade its decision on a question which affects the liberty of the citizens and agitates the country can not fail to be attended with unpropitious consequences. It will be justly held by a large portion of the people as an admission of the unconstitutionality of the act on which its judgment may be forbidden or forestalled, and may interfere with that willing acquiescence in its provisions which is necessary for the harmonious and efficient execution of any law.

For these reasons, thus briefly and imperfectly stated, and for others, of which want of time forbids the enumeration, I deem it my duty to withhold my assent from this bill, and to return it for the reconsideration of Congress.

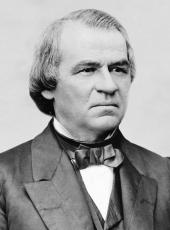

ANDREW JOHNSON.

Andrew Johnson, Veto Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/202868