To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:

I transmit to Congress a report from the Secretary of State, with copies of all the letters received from Mr. Livingston since the message to the House of Representatives of the 6th instant, of the instructions given to that minister, and of all the late correspondence with the French Government in Paris or in Washington, except a note of Mr. Serurier, which, for the reasons stated in the report, is not now communicated.

It will be seen that I have deemed it my duty to instruct Mr. Livingston to quit France with his legation and return to the United States if an appropriation for the fulfillment of the convention shall be refused by the Chambers.

The subject being now in all its present aspects before Congress, whose right it is to decide what measures are to be pursued in that event, I deem it unnecessary to make further recommendation, being confident that on their part everything will be done to maintain the rights and honor of the country which the occasion requires.

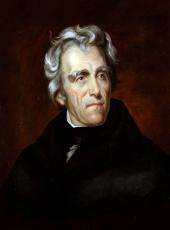

ANDREW JACKSON

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington , February 25, 1835.

The PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES:

The Secretary of State has the honor to submit to the President copies of all the letters received from Mr. Livingston since the message to the House of Representatives of the 6th instant, of the instructions given to that minister, and of all the late correspondence with the French Government in Paris or in Washington, except the last note of M. Serurier, which it has been considered necessary to submit to the Government of France before it is made public or answered, that it may be ascertained whether some exceptionable expressions are to be taken as the result of a settled purpose in that Government or as the mere ebullition of the minister's indiscretion.

JOHN FORSYTH.

Mr. Livingston to Mr. Forsyth.

No. 70.

LEGATION OF THE UNITED STATES,

Paris, January 11, 1835.

Hon. JOHN FORSYTH.

SIR: Believing that it would be important for me to receive the dispatches you might think it necessary to send with the President's message, I ventured on incurring the expense of a courier to bring it to me as soon as it should arrive at Havre. Mr. Beasley accordingly, on the arrival of the Sully , dispatched a messenger with my letters received by that vessel, and a New York newspaper containing the message, but without any communication from the Department, so that your No. 43 is still the last which I have to acknowledge. The courier arrived at 2 o'clock on the morning of the 8th. Other copies were the same morning received by the estafette, and the contents, being soon known, caused the greatest sensation, which as yet is, I think, unfavorable--the few members of the opposition who would have voted for the execution of the treaty now declaring that they can not do it under the threat of reprisals, and the great body of that party making use of the effect it has on national pride to gain proselytes from the ministerial side of the Chamber, in which I have no doubt they have in a great degree for the time succeeded.

The ministers are aware of this, and will not, I think, immediately urge the consideration of the law, as I have no doubt they were prepared to do when the message arrived. Should Congress propose commercial restrictions or determine to wait to the end of the session before they act, this will be considered as a vote against reprisals, and then the law will be proposed and I think carried. But I ought not to conceal from you that the excitement is at present very great; that their pride is deeply wounded by what they call an attempt to coerce them by threats to the payment of a sum which they persist, in opposition to the plainest proof, in declaring not to be due. This feeling is fostered by the language of our opposition papers, particularly by the Intelligencer and New York Courier, extracts from which have been sent on by Americans, declaring them to be the sentiments of a majority of the people. These, as you will see, are translated and republished here, with such comments as they might have been expected and undoubtedly were intended to produce, and if hostilities should take place between the two countries those persons may flatter themselves with having the credit of a great share in producing them. The only letter I have received from home is from one of my family. This, to my great satisfaction, informs me that the President will be supported by all parties, and I am told that this is the language of some of the opposition papers; but as they are not sent to the legation I can not tell in what degree this support can be depended upon. Whether the energetic language of the message will be made the pretext with some or be the cause with others among the deputies for rejecting the law can not, of course, be yet conjectured with any great degree of probability, but I think it will have a good effect. It has certainly raised us in the estimation of other powers, if I may judge from the demeanor of their representatives here, and my own opinion is that as soon as the first excitement subsides it will operate favorably on the counsels of France. Already some of the journals begin to change their tone, and I am much mistaken if the opposition here, finding that we are in earnest, will incur the responsibility of a rupture between the two nations, which they see must take place if the treaty be rejected. The funds experienced a considerable fall as soon as the message was known, and insurance rose. In short, it has made them feel the commercial as well as political importance of our country.

The Comte de Rigny had requested me to communicate the message to him as soon as it should be received. This I promised to do, and accordingly on the morning of the 8th, to avoid any mistake as to the mode of making the communication, I carried the paper to him myself, telling him that I had received a gazette containing a paper said to be the message of the President, which I delivered to him in compliance with my promise; but I requested him to observe that it was not an authentic paper, nor was it delivered in pursuance of instructions, nor in my official character. I thought it, for obvious reasons, necessary to be very explicit on this point, and he properly understood me, as he had not yet read the message. Little more passed at the interview, and I thought of it, but not immediately, to seek another. I shall probably, however, see him to-night, and shall then appoint some time for a further conference, of which I will by this same packet give you the result.

Mr. Middleton has just arrived from Madrid with the inscriptions for the Spanish indemnity and a draft for the first payment of interest. His instructions are, he says, to leave them with me, but as I have heard nothing from the Department I shall advise the depositing them with Rothschild to wait the directions of the president.

The importance of obtaining the earliest intelligence at this crisis of our affairs with France has reduced me to direct that my letters should be sent by the estafette from Havre, and that if any important advice should be received at such an hour in the day as would give a courier an advance of some hours over the estafette, that a special messenger should be dispatched with it.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, sir, your most obedient servant,

EDW. LIVINGSTON.

Mr. Livingston to Mr. Forsyth.

No. 71.

LEGATION OF THE UNITED STATES,

Paris, January 14, 1835.

Hon. JOHN FORSYTH.

SIR: The intended conference with the minister for foreign affairs of which I spoke to you in my last (No. 70) took place yesterday morning. I began it by expressing my regret that a communication from the President to Congress had been so much misrepresented in that part which related to France as to be construed into a measure of hostilities. It was, I said, part of a consultation between different members of our Government as to the proper course to be pursued if the legislative body of France should persevere in refusing to provide the means of complying with a treaty formally made; that the President, as was his duty, stated the facts truly and in moderate language, without any irritating comment; that in further pursuance of his official duty he declared the different modes of redress which the law of nations permitted in order to avoid hostilities, expressing, as he ought to do, his reasons for preferring one of them; that in all this there was nothing addressed to the French nation; and I likened it to a proceeding well known in the French law (a family council in which the concerns and interests are discussed), but of which in our case the debates were necessarily public; that a further elucidation of the nature of this document might be drawn from the circumstance that no instructions had been given to communicate it to the French Government, and that if a gazette containing it had been delivered it was at the request of his excellency, and expressly declared to be a private communication, not an official one. I further stated that I made this communication without instructions, merely to counteract misapprehensions and from an earnest desire to rectify errors which might have serious consequences. I added that it was very unfortunate that an earlier call of the Chambers had not been made in consequence of Mr. Serurier's promise, the noncompliance with which was of a nature to cause serious disquietude with the Government of the United States. I found immediately that this was the part of the message that had most seriously affected the King, for Comte de Rigny immediately took up the argument, endeavoring to show that the Government had acted in good faith, relying principally on the danger of a second rejection had the Chambers been called at an early day expressly for this object. I replied by repeating that the declaration made by Mr. Serurier was a positive and formal one, and that it had produced a forbearance on the part of the President to lay the state of the case before Congress. In this conference, which was a long one, we both regretted that any misunderstanding should interrupt the good intelligence of two nations having so many reasons to preserve it and so few of conflicting interests. He told me (what I knew before) that the exposition was prepared, and that the law would have been presented the day after that on which the message was received. He showed me the document, read part of it to me, and expressed regret that the language of the message prevented it being sent in. I said that I hoped the excitement would soon subside and give place to better feelings, in which I thought he joined with much sincerity. It is perhaps necessary to add that an allusion was made by me to the change of ministry in November and the reinstatement of the present ministers, which I told him I had considered as a most favorable occurrence, and that I had so expressed myself in my communications to you, but that this circumstance was unknown at Washington when the message was delivered; and I added that the hopes of success held out in the communication to which I referred and the assurances it contained that the ministers would zealously urge the adoption of the law might probably have imparted the same hopes to the President and have induced some change in the measure he had recommended, but that the formation of the Dupin ministry, if known, must have had a very bad effect on the President's mind, as many of that ministry were known to be hostile to the treaty.

When I took leave the minister requested me to reflect on the propriety of presenting a note of our conversation, which he said should be formal or otherwise, as I should desire. I told him I would do so, and inform him on the next morning by 11 o'clock. We parted, as I thought, on friendly terms, and in the evening, meeting him at the Austrian ambassador's, I told him that on reflection I had determined to wait the arrival of the packet of the 16th before I gave the note, to which he made no objection. After all this you may judge of my surprise when last night about 10 o'clock I received the letter copy of which is inclosed, and which necessarily closes my mission. In my reply I shall take care to throw the responsibility of breaking up the diplomatic intercourse between the countries where it ought to rest, and will not fail to expose the misstatements which you will observe are contained in the minister's note, both as respects my Government and myself; but the late hour at which I received the Comte de Rigny's note and the almost immediate departure of the packet may prevent my sending you a copy of my communication to him, which I shall use the utmost diligence in preparing.

The law, it is said, will be presented to-day, and I have very little doubt that it will pass. The ministerial phalanx, reenforced by those of the opposition (and they are not a few) who will not take the responsibility of involving the country in the difficulties which they now see must ensue, will be sufficient to carry the vote. The recall of Serurier and the notice to me are measures which are resorted to to save the pride of the Government and the nation.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, sir, your most obedient servant,

EDW. LIVINGSTON.

From Count de Rigny to Mr. Livingston.

(Translation.)

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS,

Paris, January 13, 1835.

Hon. EDWARD LIVINGSTON, etc.

SIR: You have well comprehended the nature of the impressions produced upon the King's Government by the message which His Excellency President Jackson addressed on the 1st of December to the Congress of the United States. Nothing certainly could have prepared us for it. Even though the complaints expressed in it had been as just as they are in reality unjust, we should still have had a right to be astonished on receiving the first communication of them in such a form.

In the explanations which I am now about to make I can not enter upon the consideration of any facts other than those occurring subsequently to the vote by which the last Chamber of Deputies refused the appropriation necessary for the payment stipulated in the treaty of July 4. However this vote may have been regarded by the Government of the United States, it is evident that by accepting (accueillant) the promise of the King's Government to bring on a second deliberation before the new legislature it had in fact postponed all discussion and all recrimination of the subject of this first refusal until another decision should have either repealed or confirmed it. This postponement therefore sets aside for the time all difficulties arising either justly or unjustly from the rejection of the treaty or from the delay by which it had been preceded; and although the message begins by enumerating them, I think proper, in order to confine myself to the matter in question, only to reply to the imputations made on account of subsequent occurrences.

The reproaches which President Jackson considers himself authorized to address to France may be summed up in a few words. The King's Government promised to present the treaty of July 4 again to the Chambers as soon as they could be assembled. They were assembled on the 31st of July, and the treaty has not yet been presented to them. Such is exactly the whole substance of the President's argumentation, and nothing can be easier than to refute it.

I may first observe that the assembling of the Chambers on the 31st of July, in obedience to a legal prescription that they should be called together within a stated period after a dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies, was nothing more than a piece of formality, and if President Jackson had attended to the internal mechanism of our administrative system he would have been convinced that the session of 1835 could not have really commenced at that session of 1834. Everyone knew beforehand that after a fortnight spent in the forms of installation it would be adjourned.

The President of the United States considers that the bill relative to the American claims should have been presented to the Chamber within that fortnight. I can not understand the propriety of this reproach. The bill was explicitly announced in the speech from the throne on the very day on which the Chambers met. This was all that was required to make known the opinion and design of the Government, and to prevent that species of moral proscription to which absolute silence would have given authority. With regard to the mere act of presentation so long before discussion could possibly take place, this proceeding would have been so unusual and extraordinary that it might have increased the unfavorable prepossessions of the public, already too numerous, without producing any real advantage in return. Above all, the result which the President had in view, of being able to announce the new vote of the Chamber of Deputies in his message, would not have been attained.

President Jackson expresses his regrets that your solicitations (instances) had not determined the King's Government to call the Chambers together at an earlier day. How soon soever they may have been called, the simplest calculation will serve to shew that the discussions in our Chambers could not have been known in the United States at the opening of Congress, and the President's regret is therefore unfounded.

Moreover, the same obstacles and the same administrative reasons which rendered a real session impossible during the months of July or August were almost equally opposed to its taking place before the last weeks of the year. The head of a government like that of the United States should be able to comprehend more clearly than anyone else those moral impossibilities which arise from the fixed character ot the principles of a constitutional regime, and to see that in such a system the administration is subject to constant and regular forms, from which no special interest, however important, can authorize a deviation.

It is, then, evident that far from meriting the reproach of failing to comply with its engagements, far from having deferred, either voluntarily or from negligence, the accomplishment of its promises, the King's Government, ever occupied in the design of fulfilling them, was only arrested for a moment by insurmountable obstacles. This appears from the explanations now given, and I must add that the greater part of them have already been presented by M. Serurier to the Government of the United States, which by its silence seemed to acknowledge their full value.

It is worthy of remark that on the 1st of December, the day on which President Jackson signed the message to Congress, and remarked with severity that nearly a month was to elapse before the assembling of the Chambers, they were in reality assembled in virtue of a royal ordinance calling them together at a period earlier than that first proposed. Their assemblage was not indeed immediately followed by the presentment of the bill relative to the American claims, but you, sir, know better than any other person the causes of this new delay. You yourself requested us not to endanger the success of this important affair by mingling its discussion with debates of a different nature, as their mere coincidence might have the effect of bringing other influences into play than those by which it should naturally be governed. By this request, sir, you clearly shewed that you had with your judicious spirit correctly appreciated the situation of things and the means of advancing the cause which you were called to defend. And permit me to add that the course which you have thought proper to adopt on this point is the best justification of that which we ourselves have for some months been pursuing in obedience to the necessities inherent in our political organization, and in order to insure as far as lies in our power the success of the new attempt which we were preparing to make in the Chamber.

However this may be, the King's Government, freed from the internal difficulties the force of which you have yourself so formally admitted, was preparing to present the bill for giving sanction to the treaty of July 4, when the strange message of December I came and obliged it again to deliberate on the course which it should pursue.

The King's Government, though deeply wounded by imputations to which I will not give a name, having demonstrated their purely gratuitous character, still does not wish to retreat absolutely from a determination already taken in a spirit of good faith and justice. How great soever may be the difficulties caused by the provocation which President Jackson has given, and by the irritation which it has produced in the public mind, it will ask the Chambers for an appropriation of twenty-five millions in order to meet the engagements of July 4; but at the same time His Majesty has considered it due to his own dignity no longer to leave his minister exposed to hear language so offensive to France. M. Serurier will receive orders to return to France.

Such, sir, are the determinations of which I am charged immediately to inform you, in order that you may make them known to the Government of the United States and that you may yourself take those measures which may seem to you to be the natural consequences of this communication. The passports which you may desire are therefore at your disposition.

Accept, sir, the assurance of my high consideration.

DE RIGNY.

Mr. Livingston to Mr. Forsyth.

No. 72.

LEGATION OF THE UNITED STATES,

Paris, January 15, 1835.

SIR: Having determined to send Mr. Brown, one of the gentlemen attached to the legation, to Havre with my dispatches, I have just time to add to them the copy of the note which I have sent to the Comte de Rigny. The course indicated by it was adopted after the best reflections I could give to the subject, and I hope will meet the approbation of the President. My first impressions were that I ought to follow my inclinations, demand my passports, and leave the Kingdom. This would at once have freed me from a situation extremely painful and embarrassing; but a closer attention convinced me that by so doing I should give to the French Government the advantage they expect to derive from the equivocal terms of their note, which, as occasions might serve, they might represent as a suggestion only, leaving upon me the responsibility of breaking up the diplomatic intercourse between the two countries if I demanded my passports; or, if I did not, and they found the course convenient, they might call it an order to depart which I had not complied with. Baron Rothschild also called on me yesterday, saying that he had conversed with the Comte de Rigny, who assured him that the note was not intended as a notice to depart, and that he would be glad to see me on the subject. I answered that I could have no verbal explanations on the subject, to which he replied that he had suggested the writing a note on the subject, but that the minister had declined any written communication. Rothschild added that he had made an appointment with the Comte de Rigny for 6 o'clock, and would see me again at night, and he called to say that there had been a misunderstanding as to the time of appointment, and that he had not seen Mr. de Rigny, but would see him this morning. But in the meantime I determined on sending my note, not only for the reasons contained in it, which appeared to me conclusive, but because I found that the course was the correct one in diplomacy, and that to ask for a passport merely because the Government near which the minister was accredited had suggested it would be considered as committing the dignity of his own; that the universal practice in such cases was to wait rite order to depart, and not by a voluntary demand of passports exonerate the foreign Government from the odium and responsibility of so violent a measure. My note will force them to take their ground. If the answer is that they intended only a suggestion which I may follow or not, as I choose, I will remain, but keep aloof until I receive your directions. If, on the other hand, I am told to depart, I will retire to Holland or England, and there wait the President's orders. In either case the derangement will be extremely expensive and my situation very disagreeable. The law was not presented yesterday, but will be to-day, and I have been informed that it is to be introduced by an expose throwing all the blame of the present state of things on Mr. Serurier and me for not truly representing the opinions of our respective Governments. They may treat their own minister as they please, but they shall not, without exposure, presume to judge of my conduct and make me the scapegoat for their sins. The truth is, they are sadly embarrassed. If the law should be rejected, I should not be surprised if they anticipated our reprisals by the seizure of our vessels in port or the attack of our ships in the Mediterranean with a superior force. I shall without delay inform Commodore Patterson of the state of things, that he may be on his guard, having already sent him a copy of the message.

I have the honor to be, sir, your obedient servant,

EDW. LIVINGSTON.

Mr. Livingston to the Count de Rigny.

LEGATION OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Paris, January 14, 1835.

His Excellency COUNT DE RIGNY, etc.:

The undersigned, envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary of the United States of America, received late last night the note of His Excellency the Count de Rigny, minister secretary of state for foreign affairs, dated the 13th instant.

The undersigned sees with great surprise as well as regret that a communication made by one branch of the Government of the United States to another, not addressed to that of His Majesty the King of the French, nor even communicated to it, is alleged as the motive for a measure which not only increases actual subjects of irritation, but which necessarily cuts off all the usual means of restoring harmony to two nations who have the same interests, commercial and political, to unite them, and none but factitious subjects for collision.

The grave matter in the body of his excellency's note demands and will receive a full answer. It is to the concluding part that his attention is now requested. The undersigned, after being informed that it is the intention of His Majesty's Government to recall Mr. Serurier, is told "that this information is given to the under signed in order that he may communicate it to his Government and in order that he may himself take those measures which may appear to him the natural result of that communication, and that in consequence thereof the passports which he might require are at his disposition." This phrase may be considered as an intimation of the course which, in the opinion of His Majesty's Government, the undersigned ought to pursue as the natural result of Mr. Serurier's recall, or it may be construed, as it seems to have been by the public, into a direction by His Majesty's Government to the minister of the United States to cease his functions and leave the country.

It is necessary in a matter involving such grave consequences that there should be no misunderstanding, the two categories demanding a line of conduct entirely different the one from the other.

In the first, he can take no directions or follow no suggestions but those given by his own Government, which he has been sent here to represent. The recall of the minister of France on the grounds alleged could not have been anticipated. Of course no instructions have been given to the undersigned on the subject, and he will not take upon himself the responsibility which he would incur by a voluntary demand of his passports, although made on the suggestion of His Majesty's Government. If this be the sense of the passage in question, the duty of the undersigned can not be mistaken. He will transmit the note of His Excellency the Comte de Rigny to his Government and wait its instructions. Widely different will be his conduct if he is informed that the conclusion of the Comte de Rigny's note is intended as a direction that he should quit the French territory. This he will without delay comply with on being so informed and on receiving the passports necessary for his protection until he shall leave the Kingdom.

Leaving the responsibility of this measure where it ought to rest, the undersigned has the honor to renew to His Excellency the Comte de Rigny the assurance, etc.

EDW'D LIVINGSTON.

Mr. Livingston to Mr. Forsyth .

No. 73.

LEGATION OF THE UNITED STATES,

Paris, January 16, 1835.

Hon. J. FORSYTH, etc.

SIR: The wind being unfavorable, I hope that this letter may arrive in time for the packet.

By the inclosed semiofficial paper you will see that a law has been presented for effecting the payment of 25,000,000 francs capital to the United States, for which the budgets of the six years next succeeding this are affected, and with a condition annexed that our Government shall have done nothing to affect the interests of France. It would seem from this that they mean to pay nothing but the capital, and that only in six years from this time; but as the law refers to the treaty for execution of which it provides, I presume the intention of the ministry can not be to make any change in it, and that the phraseology is in conformity to their usual forms At any rate, I shall, notwithstanding the situation in which I am placed in relation to this Government, endeavor to obtain some explanation on this point.

The packet of the 16th arrived, but to my great regret brought me no dispatches, and having received none subsequent to your No. 43, and that not giving me any indication of the conduct that would be expected from me in the event of such measures as might have been expected on the arrival of the President's message, I have been left altogether to the guidance of my own sense of duty under circumstances of much difficulty. I have endeavored to shape my course through them in such a way as to maintain the dignity of my Government and preserve peace, and, if possible, restore the good understanding that existed between the two countries. From the view of the motives of the President's message contained in the answer of the Globe to the article in the Intelligencer I am happy in believing that the representations I have made to the Comte de Rigny, as detailed in my No. 71, are those entertained by the Government, and that I have not, in this at least, gone further than it would have directed me to do had I been favored with your instructions.

I have no answer yet to my note to the Comte de Rigny, a copy of which was sent by my last dispatch, nor can I form any new conjecture as to the event.

The inclosed paper contains a notice that I had been received by the King. This is unfounded, and shall be contradicted. I shall not in the present state of things make my appearance at court, and only in cases where it is indispensable have any communication with the minister.

I have the honor to be, with great respect, your obedient, humble servant,

EDW. LIVINGSTON.

Mr. Forsyth to Mr. Livingston.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington, February 13, 1835.

EDWARD LIVINGSTON, Esq.

SIR: To relieve the anxiety expressed in your late communication to the Department of State as to the course to be pursued in the event of the rejection by the Chamber of Deputies of the law to appropriate funds to carry into effect the treaty of 4th July, 1831, I am directed by the President to inform you that if Congress shall adjourn without prescribing some definite course of action, as soon as it is known here that the law of appropriation has been again rejected by the French Chamber a frigate will be immediately dispatched to Havre to bring you back to the United States, with such instructions as the state of the question may then render necessary and proper.

I am, sir, etc.,

JOHN FORSYTH.

Mr. Forsyth to Mr. Livingston.

No. 49.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington , February 24, 1835.

EDWARD LIVINGSTON, Esq.,

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary.

SIR: Your dispatches to No. 73 have been received at the Department--No. 73 by yesterday's mail. Nos. 70, 71, 79 were delayed until this morning by the mismanagement of the young man to whose care they were committed by the captain of the packet Sully in New York.

In the very unexpected and unpleasant position in which you have been placed I am directed by the President to say to you that he approves of your conduct as well becoming the representative of a Government ever slow to manifest resentment and eager only to fulfill the obligations of justice and good faith, but at the same time to inform you that he should have felt no surprise and certainly would have expressed no displeasure had you yielded to the impulse of national pride and at once have quitted France, with the whole legation, on the receipt of the Count de Rigny's note of the 13th of January. M. Serurier, having received his orders, has terminated his ministerial career by the transmission of a note, a copy of which and of all the correspondence had with him is herewith inclosed. M. Pageot has been presented to me as charged with the affairs of France on the recall of the minister.

The note of the Count de Rigny having no doubt, according to your intention, received from you an appropriate reply, it is only necessary for me now to say that the Count is entirely mistaken in supposing that any explanations have been given here by M. Serurier of the causes that have led to the disregard or postponement of the engagements entered into by France after the rejection of the appropriation by the last Chamber of Deputies, and of which he was the organ. No written communication whatever has been made on the subject, and none verbally made of sufficient importance to be recorded, a silence with regard to which could have been justly the foundation of any inference that the President was satisfied that the course of the French administration was either reconcilable to the assurances given him or necessary to secure a majority of the Chamber of Deputies.

The last note of M. Serurier will be the subject of separate instructions, which will be immediately prepared and forwarded to you.

In the present position of our relations with France the President directs that if the appropriation to execute the treaty shall be or shall have been rejected by the French legislature, you forthwith quit the territory of France, with all the legation, and return to the United States by the ship of war which shall be in readiness at Havre to bring you back to your own country. If the appropriation be made, you may retire to England or Holland, leaving Mr. Barton in charge of affairs. Notify the Department of the place selected as your temporary residence and await further instructions.

I am, sir, your obedient servant,

JOHN FORSYTH.

Mr. Serurier to Mr. Forsyth.

(Translation.)

WASHINGTON, February 23, 1835 .

Hon. JOHN FORSYTH,

Secretary of State of the United States.

SIR: I have just received orders from my Government which make it necessary for me to demand of you an immediate audience. I therefore request you to name the hour at which it will suit you to receive me at the Department of State.

I have the honor to be, with great consideration, sir, your obedient, humble servant,

SERURIER.

Mr. Forsyth to Mr. Serurier.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington, February 23, 1835.

M. SERURIER,

Envoy Extraordinary, etc., of the King of the French:

Official information having been received by the President of the recall of Mr. Serurier by his Government, and the papers of the morning having announced the arrival of a French sloop of war at New York for the supposed object of carrying him from the United States, the undersigned, Secretary of State of the United States, tenders to Mr. Serurier all possible facilities in the power of this Government to afford to enable him to comply speedily with the orders he may have received or may receive.

The undersigned avails himself of the occasion to renew to Mr. Serurier the assurance of his very great consideration.

JOHN FORSYTH.

Mr. Forsyth to Mr. Serurier.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington , February 23, 1835.

The undersigned, Secretary of State of the United States, informs M. Serurier, in reply to his note of this instant, demanding the indication of an hour for an immediate audience, that he is ready to receive in writing any communication the minister of France desires to have made to the Government of the United States.

The undersigned has the honor to offer M. Serurier the assurances of his very great consideration.

JOHN FORSYTH.

Mr. Serurier to Mr. Forsyth.

(Translation.)

WASHINGTON, February 23, 1835.

Hon. JOHN FORSYTH,

Secretary of State.

SIR: My object in asking you this morning to name the hour at which it would suit you to receive me was in order that I might, in consequence of my recall as minister of His Majesty near the United States, present and accredit M. Pageot, the first secretary of this legation, as charge d' affaires of the King. This presentation, which, according to usage, I calculated on making in person, I have the honor, in compliance with the desire expressed to me by you, to make in the form which you appear to prefer.

I thank you, sir, for the facilities which you have been kind enough to afford me in the note preceding that now answered, also of this morning's date, and which crossed the letter in which I demanded an interview.

I have the honor to renew to you, sir, the assurance of my high consideration.

SERURIER.

Andrew Jackson, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/201231