To the House of Representatives:

I return herewith without my approval House bill 17707 to authorize William H. Standish to construct a dam across James River, in Stone County, Mo., and divert a portion of its waters through a tunnel into the said river again to create electric power. My reasons for not signing the bill are:

The bill gives to the grantee a valuable privilege, which by its very nature is monopolistic, and does not contain the conditions essential to protect the public interest.

In pursuance of a policy declared in my message of February 26, 1908 (S. Doc. No. 325), transmitting the report of the Inland Waterways Commission to Congress, I wrote on March 13, 1908, the following letter to the Senate Committee on Commerce:

Numerous bills granting water rights in conformity with the general act of June 21, 1906, have been introduced during the present session of Congress, and some of these have already passed. While the general act authorizes the limitation and restriction of water rights in the public interest and would seem to warrant making a reasonable charge for the benefits conferred, those bills which have come to my attention do not seem to guard the public interests adequately in these respects. The effect of granting privileges such as are conferred by these bills, as I said in a recent message, "taken together with rights already acquired under state laws, would be to give away properties of enormous value. Through lack of foresight we have formed the habit of granting without compensation extremely valuable rights, amounting to monopolies, on navigable streams and on the public domain. The repurchase at great expense of water rights thus carelessly given away without return has already begun in the East, and before long will be necessary in the West also. No rights involving water power should be granted to any corporation in perpetuity, but only for a length of time sufficient to allow them to conduct their business profitably. A reasonable charge should, of course, be made for valuable rights and privileges which they obtain from the National Government. The values for which this charge is made will ultimately, through the natural growth and orderly development of our population and industries, reach enormous amounts. A fair share of the increase should be safeguarded for the benefit of the people, from whose labor it springs. The proceeds thus secured, after the cost of administration and improvement has been met, should naturally be devoted to the development of our inland waterways." Accordingly I have decided to sign no bills hereafter which do not provide specifically for the right to fix and make a charge and for a definite limitation in time of the rights conferred.

In my veto message of April 13, 1908, returning House bill 15444, to extend the time for the construction of a dam across Rainy River, I said:

We are now at the beginning of great development in water power, Its use through electrical transmission is entering more and more largely into every element of the daily life of the people. Already the evils of monopoly are becoming manifest; already the experience of the past shows the necessity of caution in making unrestricted grants of this great power.

The present policy pursued in making these grants is unwise in giving away the property of the people in the flowing waters to individuals or organizations practically unknown, and granting in perpetuity these valuable privileges in advance of the formulation of definite plans as to their use. In some cases the grantees apparently have little or no financial or other ability to utilize the gift, and have sought it merely because it could be had for the asking.

The Rainy River Company, by an agreement in writing, approved by the War Department, subsequently promised to submit to and abide by such conditions as may be imposed by the Secretary of War, including a time limit and a reasonable charge. Only because of its compliance in this way with these conditions did the bill extending the time limit for that project finally become a law.

An amendment to the present bill expressly authorizing the Government to fix a limitation of time and impose a charge was proposed by the War Department. The letter, veto message, and amendment above referred to were considered by the Senate Committee on Commerce, as appears by the committee's report on the present bill, and the proposed amendment was characterized by the committee as a "new departure from the policy heretofore pursued in respect to legislation authorizing the construction of such dams." Their report set forth an elaborate legal argument intended to show that the Federal Government has no power to impose any charge whatever for such a privilege.

The fact that the proposed policy is new is in itself no sufficient argument against its adoption. As we are met with new conditions of industry seriously affecting the public welfare, we should not hesitate to adopt measures for the protection of the public merely because those measures are new When the public welfare is involved, Congress should resolve any reasonable doubt as to its legislative power in favor of the people and against the seekers for a special privilege.

My reason for believing that the Federal Government, in granting a license to dam a navigable river, has the power to impose any conditions it finds necessary to protect the public, including a charge and a limitation of the time, is that its consent is legally essential to an enterprise of this character. It follows that Congress can impose conditions upon its consent. This principle was clearly stated in the House of Representatives on March 28, 1908, by Mr. Williams, of Mississippi, when he said:

* * * There can be no doubt in the mind of any man seeking merely the public good and public right, independently of any desire for local legislation, of this general proposition: that whenever any sovereignty, state or federal, is required to issue a charter or a license or a consent, in order to confer powers upon individuals or corporations, it is the duty of that sovereignty in the interests of the people so to condition the grant of that power as that it shall redound to the interest of all the people, and that utilities of vast value should not be gratuitously granted to individuals or corporations and perpetually alienated from the people or the state or the government.

* * * It is admitted that this power to erect dams in navigable streams can not be exercised by anybody except by an act of Congress. Now, then, if it require an act of Congress to permit any man to put a dam in a navigable stream, then two things follow: Congress should so exercise the power in making that grant as, first, to prevent any harm to the navigability of the stream itself, and, secondly, so as to prevent any individual or any private corporation from securing through the act of Congress any uncompensated advantage of private profit.

The authority of Congress in this matter was asserted by Secretary Taft on April 17, 1908, in his report on Senator Newlands's Inland Waterways Commission bill (S. 500), where he said:

In the execution of any project and as incidental to and inseparably connected with the improvement of navigation, the power of Congress extends to the regulation of the use and development of the waters for purposes subsidiary to navigation.

And by the Solicitor-General in a memorandum prepared after a careful investigation of the subject.

Believing that the National Government has this power, I am convinced that its power ought to be exercised. The people of the country are threatened by a monopoly far more powerful, because in far closer touch with their domestic and industrial life, than anything known to our experience. A single generation will see the exhaustion of our natural resources of oil and gas and such a rise in the price of coal as will make the price of electrically transmitted water power a controlling factor in transportation, in manufacturing, and in household lighting and heating. Our water power alone, if fully developed and wisely used, is probably sufficient for our present transportation, industrial, municipal, and domestic needs. Most of it is undeveloped and is still in national or state control.

To give away, without conditions, this, one of the greatest of our resources, would be an act of folly. If we are guilty of it, our children will be forced to pay an annual return upon a capitalization based upon the highest prices which "the traffic will bear." They will find themselves face to face with powerful interests intrenched behind the doctrine of "vested rights" and strengthened by every defense which money can buy and the ingenuity of able corporation lawyers can devise. Long before that time they may and very probably will have become a consolidated interest, controlled from the great financial centers, dictating the terms upon which the citizen can conduct his business or earn his livelihood, and not amenable to the wholesome check of local opinion.

The total water power now in use by power plants in the United States is estimated by the Bureau of the Census and the Geological Survey as 5,300,000 horsepower. Information collected by the Bureau of Corporations shows that thirteen large concerns, of which the General Electric Company and the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company are most important, now hold water-power installations and advantageous power sites aggregating about 1,046,000 horsepower, where the control by these concerns is practically admitted. This is a quantity equal to over 19 per cent of the total now in use. Further evidence of a very strong nature as to additional intercorporate relations, furnished by the bureau, leads me to the conclusion that this total should be increased to 24 per cent; and still other evidence, though less conclusive, nevertheless affords reasonable ground for enlarging this estimate by 9 per cent additional. In other words, it is probable that these thirteen concerns directly or indirectly control developed water power and advantageous power sites equal to more than 33 per cent of the total water power now in use. This astonishing consolidation has taken place practically within the last five years. The movement is still in its infancy, and unless it is controlled the history of the oil industry will be repeated in the hydroelectric power industry, with results far more oppressive and disastrous for people. It is true that the great bulk of our potential water power is as yet undeveloped, but the sites which are now controlled by combinations are those which offer the greatest advantages and therefore hold a strategic position. This is certain to be strengthened by the increasing demand for power and the extension of long-distance electrical transmission.

It is, in my opinion, relatively unimportant for us to know whether or not the promoters of this particular project are affiliated with any of these great corporations. If we make an unconditional grant to this grantee, our control over it ceases. He, or any purchaser from him, will be free to sell his rights to any one of them at pleasure. The time to attach conditions and prevent monopoly is when a grant is made.

The great corporations are acting with foresight, singleness of purpose, and vigor to control the water powers of the country. They pay no attention to state boundaries and are not interested in the constitutional law affecting navigable streams except as it affords what has been aptly called a "twilight zone," where they may find a convenient refuge from any regulation whatever by the public, whether through the national or the state governments. It is significant that they are opposing the control of water power on the Desplaines River by the State of Illinois with equal vigor and with like arguments to those with which they oppose the National Government pursuing the policy I advocate. Their attitude is the same with reference to their projects upon the mountain streams of the West, where the jurisdiction of the Federal Government as the owner of the public lands and national forests is not open to question. They are demanding legislation for unconditional grants in perpetuity of land for reservoirs, conduits, power houses, and transmission lines to replace the existing statute which authorizes the administrative officers of the Government to impose conditions to protect the public when any permit is issued. Several bills for that purpose are now pending in both Houses, among them the bill, S. 6626, to subject lands owned or held by the United States to condemnation in the state courts, and the bills, H. R. 11356 and S. 2661, respectively, to grant locations and rights of way for electric and other power purposes through the public lands and reservations of the United States. These bills were either drafted by representatives of the power companies, or are similar in effect to those thus drafted. On the other hand, the administration proposes that authority be given to issue power permits for a term not to exceed fifty years, irrevocable except for breach of condition. This provision to prevent revocation would remove the only valid ground of objection to the act of 1901, which expressly makes all permits revocable at discretion. The following amendment to authorize this in national forests was inserted in last year's agricultural appropriation bill:

And hereafter permits for power plants within national forests may be made irrevocable, except for breach of condition, for such term, not exceeding fifty years, as the Secretary of Agriculture may by regulation prescribe, and land covered by such permits issued in pursuance of an application filed before entry, location or application, subsequently approved under the act of June 11, 1906, shall in perpetuity remain subject to such permit and renewals thereof.

The representatives of the power companies present in Washington during the last session agreed upon the bill above mentioned as the most favorable to their interests. At their request frequent conferences were held between them and the representatives of the administration for the purpose of reaching an agreement if possible. The companies refused to accept anything less than a grant in perpetuity and insisted that the slight charge now imposed by the Forest Service was oppressive. But they made no response to the specific proposal that the reasonableness of the charge be determined through an investigation of their business by the Bureau of Corporations.

The amendment of the agricultural bill providing for irrevocable permits being new legislation was stricken out under the House rules upon a point of order made by friends of the House bill--that is, by friends of the power companies. Yet, in the face of this record, the power companies complain that they are forced to accept revocable permits by the policy of the administration.

The new legislation sought in their own interest by some companies in the West, and the opposition of other companies in the East to proposed legislation in the public interest, have a common source and a common purpose. Their source is the rapidly growing water-power combination. Their purpose is a centralized monopoly of hydro-electric power development free of all public control. It is obvious that a monopoly of power in any community calls for strict public supervision and regulation.

The suggestion of the Senate Committee on Commerce in their report on the present bill that many of the streams for the damming of which a federal license is sought are, in fact, unnavigable is sufficiently answered in this case by the action of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce upon this very measure. As stated in the House on March 18, 1908, by Mr. Russell, of Missouri, a bill to declare this river unnavigable was rejected by that committee.

I repeat the words with which I concluded my message vetoing the Rainy River bill:

In place of the present haphazard policy of permanently alienating valuable public property we should substitute a definite policy along the following lines:

First. There should be a limited or carefully guarded grant in the nature of an option or opportunity afforded within reasonable time for development of plans and for execution of the project.

Second. Such a grant or concession should be accompanied in the act making the grant by a provision expressly making it the duty of a designated official to annul the grant if the work is not begun or plans are not carried out in accordance with the authority granted.

Third. It should also be the duty of some designated official to see to it that in approving the plans the maximum development of the navigation and power is assured, or at least that in making the plans these may not be so developed as ultimately to interfere with the better utilization of the water or complete development of the power.

Fourth. There should be a license fee or charge which, though small or nominal at the outset, can in the future be adjusted so as to secure a control in the interest of the public.

Fifth. Provision should be made for the termination of the grant or privilege at a definite time, leaving to future generations the power or authority to renew or extend the concessions in accordance with the conditions which may prevail at that time.

Further reflection suggests a sixth condition, viz:

The license should be forfeited upon proof that the licensee has joined in any conspiracy or unlawful combination in restraint of trade, as is provided for grants of coal lands in Alaska by the act of May 28, 1908.

I will sign no bill granting a privilege of this character which does not contain the substance of these conditions. I consider myself bound, as far as exercise of my executive power will allow, to do for the people, in prevention of monopoly of their resources, what I believe they would do for themselves if they were in a position to act. Accordingly I shall insist upon the conditions mentioned above not only in acts which I sign, but also in passing upon plans for use of water power presented to the executive departments for action. The imposition of conditions has received the sanction of Congress in the general act of 1906, regulating the construction of dams in navigable waters, which authorizes the imposing of "such conditions and stipulations as the Chief of Engineers and the Secretary of War may deem necessary to protect the present and future interests of the United States."

I inclose a letter from the Commissioner of Corporations, setting forth the results of his investigations and the evidence of the far-reaching plans and operations of the General Electric Company, the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, and other large concerns, for consolidation of the water powers of the country under their control. I also inclose the memorandum of the Solicitor-General above referred to.

I esteem it my duty to use every endeavor to prevent this growing monopoly, the most threatening which has ever appeared, from being fastened upon the people of this nation.

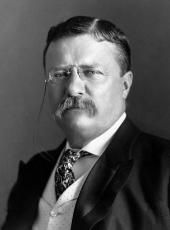

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

THE WHITE HOUSE, January 15, 1909.

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE AND LABOR,

BUREAU OF CORPORATIONS,

Washington, January 14, 1909.

SIR: I have the honor to submit herewith a report on certain features of the concentration of water powers.

The water-power situation has been greatly changed by recent improvements in electric-power transmission. Two-hundred-mile transmission is now regarded as commercially possible even in the cheaper coal areas. A two-hundred-mile radius opens an area of 120,000 square miles for the marketing of power from a given power plant.

A strong movement toward concentrating the control of water powers has accompanied this change. A very significant fact is that this concentration has taken place practically in the last five years. The chief existing concentrations are as follows:

(1) General Electric --being those power companies controlled by or affiliated with the General Electric Company or its subsidiary corporations.

(2) Westinghouse --being those similarly connected with the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company.

(3) Other concentrations of water power which can not at present be identified with either of the first two.

Inter-company relations are easily concealed. Strictly judicial proof of such community of interests is rarely obtainable, nor is it necessary for practical purposes. It is sufficient to give, as herein, the significant evidential facts, leaving the obvious deductions to be made therefrom.

Therefore the General Electric and the Westinghouse concentrations are classified in the following groups:

(a) Those where a control by one or the other of these parent companies, directly or through subsidiary corporations, is admitted.

(b) Those where such control is inferred from substantial evidence (herinafter summarized) with reasonable conclusiveness.

(c) Those where such control is at least partially indicated, though not proven, by the available evidence.

This report does not by any means assume to be a complete survey even of the present conditions of concentration. There may be many further affiliations as yet undiscovered.

The exact relations, if any, between these two groups (General Electric and Westinghouse) can not now be stated. General Electric and Westinghouse patents have been pooled since 1896, and certain individuals are interested in both General Electric and Westinghouse power companies.

(1) GENERAL ELECTRIC

The control of the General Electric Company is shown directly or through subsidiary corporations, or indicated by the appearance of the names of certain individuals unquestionably connected with the General Electric Company.

Such subsidiary corporations are:

United Electric Securities Company (Maine, 1890).

Electrical Securities Corporation (New York, 1904).

Electric Bond and Share Company (New York, 1905).

Such individuals most closely connected with General Electric Company water-power control are--

Sydney Z. Mitchell, vice-president and treasurer Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric; see above), formerly with Stone & Webster, of Boston, to be mentioned later.

J. D. Mortimer, assistant secretary Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric; see above) and director of American Gas and Electric Company.

C. N. Mason, vice-president Electrical Securities Corporation and of United Electric Securities Company (General Electric; see above).

H. L. Doherty, president American Gas and Electric Company, which in 1908 controlled at least 19 lighting and gas companies in various parts of the United States, and is, in turn, controlled by the Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric; see above).

Other names which may be mentioned are--

C. A. Coffin, president General Electric Company.

A. W. Burchard, assistant to the president, General Electric Company, and director of American Gas and Electric Company (General Electric).

C. W. Wetmore, director of Electric Bond and Share Company.

Hinsdill Parsons, vice-president General Electric Company and director of Electric Bond and Share Company.

(a) Those water-power companies which are admittedly controlled by the General Electric Company or its subsidiary companies are--

Schenectady Power Company, New York developments on the Hoosick River at Schaghticoke and Johnsonville, with a total development of 26,000 horsepower. This company is owned outright by the General Electric Company.

Carolina Power and Light Company, at Raleigh, N. C., with 4,000 horsepower installed on the Cape Fear River, and leasing power, in addition, on the Neuse River. The stock of this company is held by the Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric) and voted by Mr. J. D. Mortimer. C. Elmer Smith, of Smith interests in Westinghouse group, is also interested.

Rockingham Power Company, in North Carolina, on the Yadkin River, in process of construction, with an installation to be of 32,000 horsepower. This company is financed by the Electrical Securities Corporation (General Electric), C. N. Mason of the latter being president. C. Elmer Smith (see above) is also interested.

Animas Power and Water Company, Colorado, on the Animas River, with 8,000 horsepower installed, is controlled through the Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric).

Central Colorado Power Company, in Colorado, on the Grand River, with an installation to be of 18,000 horsepower, is also controlled through the Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric).

(b) Those water-power companies, the control of which by the General Electric Company or its subsidiary companies is reasonably inferred, are--

Montgomery Light and Water Power Company, near Montgomery, Ala., on the Tallapoosa River, with an installation of 6,000 horsepower. H. L. Doherty, president American Gas and Electric Company (General Electric), is first vice-president of this company.

The Summit County Power Company, at Dillon, Colo., with an installation of 1,600 horsepower, has Mr. H. L. Doherty, of American Gas and Electric Company (General Electric), on its directorate.

Butte Electric and Power Company (Montana), a holding company for various subsidiary power companies, to wit: Montana Power Transmission Company, Madison River Power Company, Billings and Eastern Montana Power Company. These companies comprise six water-power developments in operation, with a total installation of 43,000 horsepower. The holding company (Butte Electric) is apparently controlled jointly by C. W. Wetmore, of Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric), and C. A. Coffin, president of General Electric Company. P. E. Bisland, secretary, was formerly with Electrical Securities Corporation (General Electric).

Washington Water Power Company has three developments in Washington and Idaho, on the Spokane River, with a total installation of 61,000 horsepower. Mr. Hinsdill Parsons, vice-president of General Electric Company and Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric), is on the directorate.

Great Western Power Company, in California, on the north fork of the Feather River in Butte County, with an installed capacity of 53,000 horsepower. On its directorate are Mr. A. W. Burchard, of the General Electric Company, and Mr. A. C. Bedford, of the Standard Oil Company.

(c) Control partially indicated.

There are also a number of other water-power companies, with a total of about 420,000 horsepower (including installations and power sites), whose connection with the General Electric Company is at least partially indicated, though the evidence thereto is by no means conclusive.

(2) WESTINGHOUSE.

The Westinghouse group contains the following companies:

The Security Investment Company;

Electric Properties Company (New York, 1906), successor to Westinghouse, Church, Kerr & Co.; and the

Smith interests, represented by C. Elmer Smith and S. Fahs Smith, of S. Morgan Smith Company, important manufacturers of water turbines. While C. Elmer Smith is interested in at least two General Electric power companies (Carolina and Rockingham; see above), the Smith interests seem especially harmonious with the Westinghouse group, and are so classified.

The individual names most prominently identified are:

John F. Wallace, of New York, president Electric Properties Company.

George C. Smith, of Pittsburg and New York. vice-president and director of the Electric Properties Company.

C. Elmer Smith, of Smith interests.

(a) Those power companies which are admittedly Westinghouse are:

Atlanta Water and Electric Power Company, on the Chattahoochee River above Atlanta, Ca., with an installation of 17,000 horsepower. C. Elmer Smith is president and George C. Smith and S. Fahs Smith directors.

Ontario Power Company of Niagara Falls, a Canadian corporation on the Canadian side, with an installation of 66,000 horsepower. Together with its distributing company in the United States, the Niagara, Lockport, and Ontario Power Company, it is known as a Westinghouse concern, H. H. Westhighouse being president of the latter, and the majority of its stock being voted by the Electric Power Securities Company of New York, a construction company owned by Westinghouse interests.

(b) Those power companies whose connection with Westinghouse interests is inferred from substantial evidence (hereinafter summarized) are:

Albany Power and Manufacturing Company, near Albany, with 3,500 horsepower installed, on the Kinchatoonee, and owning besides a site on the Flint River, estimated at 10,000 horsepower, has for its vice-president C. Elmer Smith (Smith interests).

Electric Manufacturing and Power Company, on the Broad River, near Spartanburg, S.C., with 11,500 horsepower installed, has on its directorate E. H. Jennings, of Pittsburg, a director of the Electric Properties Company (Westinghouse).

Savannah River Power Company, on the Savannah River, near Anderson, S.C., has an installed development of 3,000 horsepower, and owns besides a site of 6,000 horsepower. This company has on its directorate C. Elmer Smith (Smith interests).

Gainesville Electric Railway Company, with 1,500 horsepower installed, on the Chestagee River, a tributary of the Chattahoochee, near Gainesville, Ga. Eighty-five per cent of its stock is owned by the North Georgia Electric Company (Smith interests).

North Georgia Electric Company; one development of 3,000 horsepower and at least seven other power sites on the upper waters of the Chattahoochee, and through the Etowah Power Company, personally identified with itself, it owns four other sites on the headwaters of the Coosa River. C. Elmer Smith is vice-president.

Chattanooga and Tennessee River Power Company, in process of construction at Hale Bar on the Tennessee River, below Chattanooga, in cooperation with the War Department, by which the Government obtains slack-water navigation. The company in return receives ownership of the power of 58,000 horsepower to be installed. This company is being personally financed by A. N. Brady, of New York. a director of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. Mr. Brady is also a director of the American Tobacco Company, whose interests control the Southern Power Company (see below).

Northern Colorado Power Company, which has a steam development at Lafayette, Colo., and is projecting power plants on the Platte, has John F. Wallace and George C. Smith on its directorate (Westinghouse).

(c) Control partially indicated.

There are also a number of other water-power companies, with a total of about 102,000 horsepower (including installations and sites) whose connection with the Westinghouse Company is at least partially indicated, though the evidence thereto is by no means conclusive.

(3) OTHER CONCENTRATIONS.

The General Electric and Westinghouse companies present the most important examples of water-power concentration, as above set forth. There are, however, a number of other companies and interests further showing the facts and tendencies of concentration.

The more important instances are as follows:

The Gould interests, located in Virginia, with undeveloped powers and power sites on the James and Appomattox amounting to 20,000 horsepower, and owning besides other sites on the Appomattox and Rappahannock rivers.

Southern Power Company, the largest operating power company in the South, has 90,000 horsepower installed in three developments, 31,000 horsepower in process of construction, and at least seven other power sites in North Carolina and South Carolina, with a total potential capacity of 75,000 horsepower. This company supplies 110 cotton mills and other factories in at least 28 towns, including a population of about 200,000. Messrs. B. N. Duke, J. B. Duke, and Junius Parker, of the American Tobacco Company, are officers and directors.

Stone & Webster, of Boston. This concern owns and controls powers and sites in Florida, Georgia, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, and in the Puget Sound region, with a total capacity of about 150,000 horsepower. Mr. Sydney Z. Mitchell, now of the Electric Bond and Share Company (General Electric), was formerly connected with Stone & Webster, and in 1908, according to Moody's Manual, 1908, was still a director in three of Stone & Webster's subsidiary corporations, to wit, Puget Sound Electric Railway, Tacoma Railway and Power Company, and Puget Sound Power Company.

Charles H. Baker interests; having proposed developments in Alabama estimated at 130,000 horsepower.

Commonwealth Power Company, together with the Grand Rapids-Muskegon Power Company (both under same interests), controlling 13 developed water powers in Michigan, with a total installation of 43,000 horsepower. A harmonious connection apparently exists with the Eastern Michigan Power Company, which controls all the power sites on the Au Sable River, Michigan.

United Missouri River Power Company, a holding company controlling at least three subsidiaries, which, with a closely related company, have five developed powers and one in construction, making a total of 57,500 horsepower.

Portland General Electric Company, with developments on the Clackamas and Willamette rivers amounting to 22,500 horsepower, near Portland, Ore. A. C. Bedford, a director of the Standard Oil Company, is president, and F. D. Pratt, also of the Standard Oil Company, is a director.

Pacific Gas and Electric Company. This is a very important holding company of the California Gas and Electric Corporation and the San Francisco Gas and Electric Company. These two latter companies in turn represent the consolidation or acquisition of the stock or property of over thirty power or power-distributing companies in California. They control 11 water-power developments, with a total installed plant of 118,000 horsepower.

Pacific Light and Power Company, with another company controlled by the same interests, known as the Huntington interests, represent eight developments in California, with a total of 30,000 horsepower. Henry E. Huntington is vice-president and Howard E. Huntington a director.

Edison Electric Company, with six developments in California and a total of 33,000 horsepower.

Hudson River Electric Power Company, a holding company for the Hudson River Water Power Company, Hudson River Power Transmission Company, Empire State Power Company, with developments at Spiers Falls and Mechanicsville on the upper Hudson, and Schoharie Creek near Amsterdam, N. Y., amounting to 45,000 horsepower installed, and sites owned in the Mohawk, Sacandaga, and Upper Hudson valleys, amounting to 30,000 horsepower, or a total of 75,000 horsepower. C. Elmer Smith was director of the holding company to within a year.

SUMMARY.

An estimate of the water power, developed and potential, now controlled by the General Electric interests, admitted or sufficiently proven, is about 252,000 horsepower; by the Westinghouse interests, similarly known, about 180,000 horsepower, and by other large power companies, 875,000 horsepower. This makes a total of 1,307,000 horsepower. Adding the horsepowers of the third class (c), those whose connection with these two great interests is at least probable, to wit, 520,000 horsepower, we have a small group of 13 selected companies or interests controlling a total of 1,827,000 horsepower.

Assuming that the water power at present in use by water-power plants in the United States is 5,300,000 horsepower, as estimated by the United States Census and Geological Survey from figures of installation, it is seen that approximately a quantity of horsepower equal to more than 33 per cent of that amount is now probably controlled by this small group of interests. Furthermore, this percentage by no means tells the whole truth. The foregoing powers naturally represent a majority of the best power sites. These sites are strategic points for large power and market control. Poorer sites will not generally be developed until these strategic sites are developed to their full capacity. And should these strategic sites be "coupled up" they become still more strategic. There are powerful economic reasons for such coupling. The great problem of water-power companies is that of the "uneven load," and not only of an uneven load but of an uneven source of power, because of the fluctuating flow of the stream. A coupling-up utilizes not only the different storages in the same drainage basin, but, of still greater import, the different drainage flows of different basins. Also, by coupling-up, powers which have largely "day loads" can at night help out other powers which have largely "night loads," and vice versa. Coupling-up is rapidly in progress in the United States. The Niagara Falls Power Company and the Canadian Niagara Power Company are coupled. The Southern Power Company, in North Carolina and South Carolina; the Commonwealth Power Company, in Michigan; the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, the Pacific Light and Power Company, and the Edison Electric Company, in California--each concern has its various developments coupled-up into one unit.

The economic reasons urging water-power concentration are thus obvious. The facts set forth above show the very rapid and very recent concentration that has already occurred, practically all in the last five years. These economic reasons and business facts indicate clearly the further progress toward concentration that is likely to occur in the near future. It is obvious that the effect on the public of such present and future conditions is a matter for serious public consideration.

Very respectfully yours,

HERBERT KNOX SMITH,

Commissioner of Corporations.

THE PRESIDENT.

(Memorandum by the Solicitor-General on the power of Congress, in granting licenses for dams and other structures in navigable streams, to impose certain conditions.)

MAY 11, 1908.

The general principle that a grant of property or of any right or privilege may be upon conditions needs no citation of authority. If a grantor may give or withhold, he may give upon terms. The authority to make a grant generally carries with it the authority to withhold, to impose conditions, to modify, and to terminate.

The Pacific Railroad charters contained the condition that the government service in transporting mails, troops, supplies, etc., should have the preference, and in some cases in consideration of the land grants the transportation was to be free from all toll or other charge upon any property or troops of the United States. (Sec. 6, act of July 1, 1862, 12 Stat., 489, 493, Union Pacific; sec. 3, act of March 3, 1863, id., 772, 773, Missouri Pacific; see also act of July 1, 1864, 13 Star., 339; sec. 11, act of July 2, 1864, id., 365, 370, Northern Pacific, in which Congress reserved the right to restrict charges for government transportation; sec. 11, act of July 27, 1866, 14 Stat., 292, 297.) In the acts to aid in the construction of telegraph lines "to secure to the Government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes," it was provided that the government business shall have priority over all other business, and shall be sent at rates to be annually fixed by the postmaster-General (e.g., sec. 2, act of July 24, 1866, 14 Stat., 221).

These charters, licenses, and grants were made under the federal authority over interstate commerce and over post-roads, and manifestly the reservations or conditions were germane to the grants and for the benefit of the whole people, being for the benefit of their government. In reference to the proposal in connection with the control of the Government over navigation and the improvement of inland waterways to limit permissive licenses for dams and other structures to a definite time, and to impose a charge for the power developed or for any use of the surplus water, it is objected that this is to usurp power or to pervert and misapply federal power to an end or object to which it has no relation.

There is no doubt of the national power over navigation, and the inquiry presupposes governmental control as proposed and the grant of licenses only in navigable streams. The question is wholly one of power. No one questions the power of Congress over navigation and navigable waters as a branch of its power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and the power fails here, it is said, because of the lack of connection between navigation and the purpose for which the power is to be used, because to impose terms for the use of water made possible by structures in aid of navigation or structures permitted and licensed as not seriously interfering with navigation, by limiting the time during which that privilege or right shall be enjoyed and by imposing a charge for it, is not germane to the only branch of power which Congress may constitutionally exercise here; that is, the power over navigation. It is said that the State and not the United States controls and administers the rights which riparian owners may possess in the water or the use of the water; that riparian owners do possess rights of property which may not be taken from them under the guise of a power to regulate navigation; and that the States and not the United States are clothed as matter of sovereignty and dominion with the power over and the property in the waters themselves and the beds of the streams.

But first and in general, whatever the rights of the individual riparian or the particular State, which we will examine later, there is no doubt whatever that the federal authority over navigation is paramount to everything within its sphere, and the only question here would be the truth as a fact of the federal exercise of power, whether it was actually the authority over navigation which is being exercised, and whether the proposed law or laws which carry that authority into effect are a legitimate means of exercising the power, and whether there is a genuine and legitimate relation between the power and the objects and purposes to which it is applied.

The question is, then, as to the reality and degree of connection between the power and the method and effect of its exercise. In the recent measures proposed for acquiring lands in the Southern Appalachian and White mountains for national forest purposes the test is that the land shall be situated on the watersheds of navigable streams and shall be more valuable for the regulation of stream flow than for other purposes. The House committee reports show, amid divergent views as to whether the particular thing proposed was in fact a legitimate exercise of the power, that all agreed Congress, having an unquestioned right to improve navigable streams, may take land for that purpose whenever in the judgment of Congress it is necessary to the proper exercise of the power. Thus the committee resolved that the Federal Government has no power to acquire lands within a State solely for forest reserves, but under its constitutional power over navigation may appropriate for the purchase of lands for forest reserves in a State, provided it clearly appears that such reserves have a direct and substantial connection with the conservation and improvement of the navigability of a river actually navigable in whole or in part; and that any appropriation made therefor is limited to that purpose (Mr. Jenkins). Mr. Parker did not concur, thinking the question at least doubtful, and that the United States has no interest in rivers except for purposes of navigation, and "it may fairly be said that the rivers of the Atlantic slope are not navigable above tidal flow."

Messrs. Littlefield, Diekema, and Bannon have no doubt of the power, and think that if reforesting the watershed at its source is an appropriate means plainly adapted to that end of preventing the depositing in the river of accumulations that would obstruct its navigable portion, Congress has the right to acquire and control for that purpose. But the improvement of navigability in this way by increasing the flow of the water must not be theoretical, but physical, tangible, actual, and substantial, demonstrable by satisfactory, competent testimony in order to justify an appropriation. And the protection and improvement of navigability must also be the real, effective, sole, and not the incidental, purpose of the appropriation.

Mr. Brantley holds that Congress has the constitutional power to acquire lands and forest reserves in a State by purchase, condemnation, or otherwise, as an aid to navigation, if it be made to appear to Congress that such reserves would materially or substantially aid navigation.

It is thus evident from all these views that there is no doubt of the power, and that the only real question is whether navigability is substantially aided, or whether the proposed exercise of the power is too remote and fanciful to commend itself to the judgment of Congress as an appropriate means.

It is to be said respecting structures in navigable streams that the legislation of Congress has passed through an evolution up to the point now reached and the proposals now made. The Government has built many public works in aid of navigation where the improvement and protection were obvious by dams, locks, and canals, an example of which is the canalization of the St. Mary's River on the connecting waters of the Great Lakes just as they issue from Lake Superior and on the international boundary between this country and Canada. Another feature of this evolution may be noted here in that region. The United States granted an easement for a right of way through public reserved lands of the United States to the State of Michigan for purposes of this canal, and then the state ministration was surrendered and all rights reconveyed to the United States so that locks and other works in aid of navigation there might be undertaken commensurate with the power and interests of the nation and adequate for the enormous traffic passing that point and still increasing by leaps and bounds.

Sometimes Congress commits to municipalities or corporations or private individuals the construction and operation of works in aid navigation where actual and practical navigation already exists and is being improved, as by the act of April 26, 1904 (33 Stat., 309); and at points along such reaches of the stream where, except for the government canals and other works in aid of navigation, the river itself is not actually navigable (e.g., act of May 9, 1906, 34 Stat., 183; id., 211, 1288; act of March 6, 1906, 34 Stat., 52; extract from river and harbor act of March 2, 1907, 34 Slat., 1073, 1094); or permits structures for power development at points in rivers where government plans of navigation improvement by locks, dams, and canals have already been adopted and the work begun, as at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River, or on the Coosa River in Alabama; or gives the right to build a dam, maintain and operate power stations in connection with it in consideration of the construction of locks, and a dry dock in place of existing ones owned and operated by the United States, namely, Des Moines Rapids Canal, act of February 9, 1905 (33 Stat., 712); or the particular structure is also subjected to the provisions of the general dam act of June 21, 1906, hereafter to be referred to (act of February 25, 1907, 34 Stat., 929; act of April 23, 1906, id., 130. act of March 3, 1905, 33 Stat., 1004).

It is difficult to see any difference in principle between such a case granting the right to develop and use power in consideration of improving navigation facilities and the imposition of any other reasonable amount or kind of charge. Of course, an illegal power can not be justified because it has already been illegally exercised; but the actual exercise of the power and the development of the matter under the acts of Congress are instructive and significant.

In the numerous cases where permissive licenses have been given to build dams or other structures in navigable streams at points where they are not at present actually navigable or practically used for purposes of navigation there is no question, first, that the stream being navigable as an integral thing or unit, the control over it as such belongs to Congress and not to the State. The action of Congress is an exclusion of any state authority which might otherwise exist, and the theory appears to be that although the structure may be an interference with the existing navigability, such as it is, it is, in the opinion of Congress, a reasonable interference. Congress by the very fact of its interposition and grant of license is looking to navigable character alone and to the future improvement or protection of navigation, and accordingly invariably Congress either imposes the necessity of making a proper lock or dam in all such cases, and sluices, or reserves the right to compel the construction in the future of a suitable lock for navigation purposes in connection therewith, subjects all plans to the approval of the Secretary of War, reserves the right at any time to take possession of the dam without compensation and control the same for purposes of navigation, and imposes the duty of building in connection with the dam or canal or other works a wagon and foot bridge if desired in connection therewith for the purpose of travel; and the right to alter, amend, and repeal the grant or to require the alteration or removal of the structure is also reserved (act of June 4, 1906, 34 Stat., 265; act of June 16, 1906, id., 296).

Not all these conditions appear in every such grant or license, but they all do appear from time to time in different acts, and it is clear that whether Congress is itself actually improving and protecting navigation or authorizing some other agency or instrumentality to do so in its behalf, or permitting a reasonable obstruction in the particular stream and place when the interests of navigation do not forbid, Congress is proceeding altogether under that power, expressly reserves full control in that behalf, and either provides for locks and canals in the particular construction authorized as part of the authority to build, or else reserves the right to do so whenever the interests of navigation demand. There are many instances of such acts. I cite a few: Act of July 3, 1886 (24 Stat., 123); act of February 27, 1899 (30 Stat., 904); act of June 14, 1906 (34 Stat., 266).

These other points are to be observed in this development of the law. The present and future interests of the United States are provided for (sec. 1, act of June 21, 1906, 34 Stat., 386); uniformly there is a stipulation that the United States shall be entitled to free use of the water power developed (id., and many other acts); a general limit of time for construction is imposed (id.); it is a standing provision and reservation that the construction authorized shall not interfere with navigation; the licensee shall be liable to riparians for damages caused by overflow, etc.; the dam and works authorized shall be limited to the use of the surplus water not required for navigation (act of May 9, 1906, 34 Stat., 183); Congress may revoke, and there are provisions for forfeiture for breach of conditions. Such provisions and conditions, as I have said, appear throughout all these statutes.

Note also the special provisions in the river and harbor act of June 13, 1902 (32 Stat., 358), and in the act of June 28, 1902 (id., 408), by which leases or licenses for the use of water power in the Cumberland River, Tennessee, may be granted by the Secretary of War to the highest responsible bidders, after advertisement, limited to the use of the surplus water not required for navigation and under the condition that no structures shall be built and no operations conducted which shall injure navigation in any manner or interfere with the operations of the Government or impair the usefulness of any government improvement for the benefit of navigation.

In some cases these acts provide not only for sluiceways for logs, etc., but for sluiceways and ladders for fish. It might be as reasonably objected that the United States could make no such condition in connection with its licenses for the preservation of fish in the interest of all the people, because that was solely a matter of state control and largely a matter of riparian right, as to say that it could not impose conditions and charges respecting the power developed by the surplus water.

Occasionally the title of the act recognizes the joint purpose or the collateral and subsidiary incident of power. Thus, an act of May 1, 1906 (34 Stat., 155), relative to the Rock River license, is entitled "An act permitting the building of dams, etc., in aid of navigation and for the development of water power."

In an act of June 29, 1906 (34 Stat., 628), permitting the erection of a lock and dam in aid of navigation in the White River, Arkansas, it is provided that the licensee shall purchase and pay for certain lands necessary for the successful construction and operation of the lock and dam and leave them to the United States, and that, in consideration of the construction of these structures free of cost to the United States, the United States grants to the licensee the rights possessed by it to use the water power produced by the dam and to convert the same into electric power or otherwise utilize it for a period of ninety-nine years, but to furnish to the United States, free of cost, sufficient power to operate the locks and to light the United States buildings and grounds.

Another instance of authority granted to the Secretary of War to make leases or issue licenses for the use of water power is shown by the river and harbor act of September 19, 1890, respecting the Green and Barren rivers.

Without dwelling further on this subject, it is plain that considering this whole body of laws, the United States is legitimately exercising the power over interstate commerce under the heading of the improvement and protection of navigation, and is imposing proper--that is, not only just, but legal--terms, conditions, and reservations, and as a question of power this is as clearly true when the United States licenses a structure which is a temporary and partial obstruction to navigation at some point where the Government is not yet ready to complete and unify the navigable use of the stream, as where the Government is itself developing an actual plant for the improvement of navigation by constructing the appropriate works. And the connection between the power and its application is as evident and germane even when water power is developed and a charge made for it, because, while that or some other use of the water outside navigation use is the primary or the sole object of the licensee and the navigation use is only incidental to that use, so far as the licensee is concerned, that other use from the standpoint of the Government and the people at large is always and only incidental to the improvement and protection of navigation and that use. This is true as a real fact and principle controlling the subject, even if the ultimate improvement of navigation--the actual navigation use, that is--is remote in time and as a practical undertaking, and is contemplated, so to speak, far ahead.

State law, it is true, in general determines the title of riparian owners in the beds of both navigable and nonnavigable streams, and their rights of user in the flowing water. This riparian property and right, which, respecting title to the beds of nonnavigable streams as extending ad filum aquae, is pretty uniform throughout the States, varies as to navigable streams according as States have followed the common-law rule of stopping the private title at the shore, or having followed the rule on unnavigable waters and extended it to the middle thread of the stream. Regarding the rights of the riparian in the water, the rules vary from the common-law doctrine in the humid States that the upland owner is entitled to the flow of the water as it was accustomed to flow to the doctrine of prior appropriation for beneficial use in the arid States, including the combination of the two doctrines known as the California rule. But always and everywhere the use must be reasonable, and there is an order of preference in the uses beginning with domestic use. Even on public navigable rivers the riparian owner has many rights of riser subject to the limitation that his use must be reasonable, so as not to injure the rights of others above or below him on the stream, and subject to the public easement of navigation, and generally to the public right of fishing. The riparian owner has, for instance, the right of access, but when the paramount control over navigation interferes this is a barren right and he is not entitled to compensation; and it seems that even in States where he has the title to the submerged lands out to the middle of the stream the title is a bare, technical title not available for access or any other purpose, or at least not entitling him to compensation if the United States, for any lawful purpose, should appropriate and occupy the subaqueous lands. (Scranton v. Wheeler, 179 U. S., 141.)

So much for the private and individual interest of the riparian owner; and it is to be observed respecting the pending proposals that such rights are always capable of being asserted in a court of law; that presumably the Government or the government licensee will have acquired the necessary riparian ownership, and that provision is expressly made in all statutes of this character for compensation by the licensee to the riparian or others for all damages caused.

Now, as to the state interest, there is no doubt that a State may undertake the improvement of a navigable stream within her borders, or license structures over it or in it, until the United States under legislation by Congress assumes jurisdiction. In this matter and in similar instances the Supreme Court has held that there is a concurrent function and power, and that nonaction by Congress amounts to permission to the State to occupy the field. (Willson et al. v. The Black Bird Creek Marsh Co., 2 Pet., 245, 252-253; The Passaic Bridges, 3 Wall., 793; Pound v. Turck, 95 U. S., 463; Escanaba Co. v. Chicago, 107 U. S., 683; Morgan v. Louisiana, 118 U. S., 465; New York, etc., R. R. Co. v. New York, 165 U. S., 631; United States v. Rio Grande Irrigation Co., 174 U. S., 690, 703.) But of course it can not be admitted that a State has any jurisdiction or control whatsoever after Congress has determined that the stream is navigable (whether it is explicitly so denominated or not) and proceeds to improve or protect the navigation or navigable capacity. Then the federal jurisdiction becomes plenary, paramount, and exclusive. The very fact that Congress has legislated as it has done respecting the various streams and waters embraced in the legislation above reviewed is conclusive proof that the national jurisdiction has completely ousted state jurisdiction over those waters and at those points. This seems to be the view of the States themselves and on all hands, and I do not understand that this position is disputed even by those who claim that for purposes of power and all other incidental uses of the water other than for navigation the state authority is supreme and exclusive.

It is a mistake to suppose that the federal jurisdiction and the navigability are doubtful because the stream may not be navigable now at the particular point. It is to make it navigable at some time, even if a remote future is contemplated, and slow progress toward a comprehensive and unifying plan--it is to improve navigation, to increase navigable capacity, and in the meantime to protect navigation that the national power interposes. In many senses a navigable stream is a unit. It is none the less a navigable stream because there is an obstruction at a particular point (The Montello, 20 Wall., 430), being navigable above or below or both. And while the test of navigability at any particular point is whether the stream is navigable in fact, the upper reaches of a stream and the preservation and maintenance of flow at the sources, although the stream is not navigable there, are clearly within the scope of the power as directed to the continuing protection as well as the immediate improvement of navigation. The case of United States v. Rio Grande Irrigation Co. (174 U. S., 690), by the necessary effect of the final order at page 710, sustains the contention that the United States may interpose to control or prevent the irrigation or other use of water above the limit of navigability, if it shall appear as a fact that such use impairs the navigable capacity over that portion of the stream where navigation does exist.

The preliminary report of the Inland Waterways Commission with the President's message transmitting it to Congress, and the bill introduced in the Senate by Mr. Newlands (S. 500), with the report and recommendations of the Secretary of War upon the same, are very instructive and significant in this matter. The bill reflects and embodies the main ideas and recommendations of the report and will alone serve the purposes of our consideration after one or two references to the report. The report and the President's message point out that a river system from the forest headwaters to the mouth is a unit and that navigation of the lower reaches can not be fully developed without the control of floods and low waters by storage and drainage; that navigable channels are directly concerned with the protection of source waters and with soil erosion which forms bars and shoals from the richest portions of farms; and that the uses of a stream for domestic and municipal supply, for power and often for irrigation, must be taken into account. The development of waterways and the conservation of forests are pressing needs and are interdependent. The systematic development of interstate commerce by improvement of inland waterways should proceed in coordination with all other uses of the waters and benefit to be derived from them, which constitute a public asset of incalculable value. The report notes that irrigation projects involving the storage of flood waters (in which, of course, reclamation of arid lands is the chief and primary object) create canals as well as tend to purify and clarify waters and to conserve supply by seepage during droughts; that on the other hand works designed to improve navigation commonly produce headwater and develop power; that western projects are "chiefly thus far for irrigation, but prospectively for navigation and power."

Accordingly the great central idea of Mr. Newlands's measure is the conservation and correlation of the natural resources of the country in navigable waters which are national resources, because essentially dependent upon and developed from the preservation and regulation of stream flow and the improvement of navigation. For example, section 2 of the bill provides for examinations, surveys, and investigations--

with a view to the promotion of transportation; and to consider and coordinate the questions of irrigation, swamp-land reclamation, clarification of streams, utilization of water power, prevention of soil waste, protection of forests, regulation of flow, control of floods, transfer facilities and sites, and the regulation and control thereof, and such other questions regarding waterways as are related to the development of rivers, lakes, and canals for the purposes of commerce.

And again, by section 6, the projects authorized and begun under section 5--

may include such collateral works for the irrigation of arid lands (for reclamation and conservation as specified) and for the utilization of water power as may be deemed advisable in connection with the development of a channel for navigation, or as aiding in a compensatory way in the diminution of the cost of such project.

Section 7 authorizes the commission to be appointed "to enter into cooperation with States, municipalities, communities, corporations, and individuals in such collateral works."

The report of the Secretary of War on this bill, dated April 17, substantially and by inference approves its purpose and general provisions, while making certain specific suggestions. That report notes the provision for coordination between navigation and other uses of the waters in connection with their improvement for the promotion of commerce among the States, and the provision for cooperation with States, municipalities, etc., so as to promote "union of interests through mutual beneficial cooperation," which "feature is recognized by the War Department as highly desirable." The report also notes the provision for correlating the existing agencies in the d

Theodore Roosevelt, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/206675