Thank you. It is a pleasure to be here. I want to keep my remarks brief so that I can quickly get to your questions, comments or insults. Let me begin by offering a few thoughts about the press's role in political campaigns. Long ago in my career, I made a decision to be as accessible to the press as the press would prefer me to be, and, perhaps, even more than they would prefer. There have been days on the back of the bus when I couldn't help but notice the relief that spread among reporters when, after hours had passed, our conversation exhausted the day's questions of policy and politics and finally turned to ball scores, vacation plans, and the amusing eating and sleeping habits of my friend, Lindsey Graham. For those of you interested in what those habits might entail, Liz Sidoti, Libby Quaid and Dave Espo can fill you in.

Running campaigns under the frequent if not constant scrutiny of the press can be challenging. And there have been days when I wished you had been somewhere else when I made comments that were interpreted in ways I didn't intend and took on a longer life than I would have preferred. Occasionally, the penalties a candidate suffers by granting widespread access can reinforce a campaign's natural tendencies to avoid risk and closely control its message. There have been times when my enthusiasm in arguing a point and my glibness have had an effect that caused me to appreciate the qualities of tight message discipline and my staff to become distraught because I answered a question simply because I was asked. I confess also that on occasion, perhaps many occasions, I have felt reporters' questions, their redundancy and sometimes adversarial quality, were intended more at producing candidate fatigue and, consequently, mistakes than the enlightenment of your readers.

These aren't trivial worries, and they do tend to support arguments for a more careful approach to talking to you. I want to win this election as do my opponents, and Americans have always taken the view that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Thus, campaigns naturally look suspiciously at the more circuitous route to success that wends and sometimes loses its way through the obstacle course of the candidate's exchanges with the press. But I've become rather accustomed to it. And though my campaign certainly took a circuitous route to securing my party's nomination -- to put it charitably -- I don't intend to change that particular habit of a lifetime.

I believe in giving great access to the press for three reasons. First, I much prefer long back and forths, where reporters have multiple follow ups and I have an opportunity to explain my views in greater detail -- and, occasionally to correct any initial mistakes I might have made in communicating them -- than is allowed in the short exchanges and bright lights of the press avail. The dynamics of the avail, in my opinion, tend to produce more heat than light on your part and excessive caution on the candidate's part. Reporters have one, maybe two shots at me, and they want it to count, by which I mean they would like to catch me in a mistake, a discrepancy or a less than artful expression. And candidates tend to approach them with the primary intention of not saying anything beyond a single message or not saying anything newsworthy at all.

Second, I think reporters are better able to meet their first responsibility of ensuring an informed citizenry if they are allowed to press a candidate for more than a gotcha quote or a comment on whatever the cable driven news environment has decided is the process story of the day.

Last, and most importantly, the responsibility of an informed citizenry is as much my responsibility as it is yours. I don't believe in deceiving voters about my positions, my beliefs or how I would govern this country were I to have the extraordinary privilege of serving as President. I want voters to know and understand my positions. I intend to stand by them, to defend them and even, at times, to engage in spirited debate with voters about them. But I want them to know what and why I believe the things I believe. And I think the press wants voters to know that as well, even though, at times, my views can suffer from your translation of them, sometimes more through my fault than yours. That is why I prefer the townhall format to other forms of communication with the voters. And that is why I make myself regularly available to all of you. I will screw up sometimes, and, frankly, so will you. But on the whole, you, I and, most importantly, the American people are better served by the openness and accountability that direct, lengthy and frequent exchanges with the press produces. And I will take my chances with you and trust in the American people to get it right in the end.

In the spirit of that commitment to communicating my views fully and honestly to you, I want to address quickly an issue I know is important to you, the so-called "shield law" pending before Congress. I have had a hard time deciding whether to support or oppose it. To be very candid, but with no wish to offend you, I must confess there have been times when I worry that the press' interest in getting a scoop occasionally conflicts with other important priorities, even the first concern of every American -- the security of our nation. I take a very, very dim view of stories that disclose classified information that unnecessarily threatens or makes it more difficult to protect the physical security of Americans. I think that has happened before, rarely, but it has happened. I think the New York Times' decision to disclose surveillance programs to monitor the conversations of people who wish to do us harm came too close to crossing that line. And I understand completely why the government charged with defending our security would want to discourage that from happening and hold the people who disclosed that damaging information accountable for their action.

The shield law would give great license to you and your sources, with few restrictions, to do as you please no matter the stakes involved and without fear of personal consequences beyond the rebuke of your individual consciences. It is, frankly, a license to do harm, perhaps serious harm. But it also a license to do good; to disclose injustice and unlawfulness and inequities; and to encourage their swift correction. The First Amendment is based in that recognition, and I am, despite the criticism of campaign finance reform opponents, committed to that essential right of a free society. I know that the press that disclosed security secrets that should have remained so also revealed the disgrace of Abu Ghraib, a disgrace that made it much harder to protect the American people from harm. Thus, despite concerns I have about the legislation, I have narrowly decided to support it. I respect those of my colleagues who have decided not to; appreciate very much the concerns that have informed their position, and encourage further negotiations to address those concerns. But if the vote were held today, I would vote yes. By so doing, I and others, on behalf of the people we represent, are willing to invest in the press a very solemn trust that in the use of confidential sources you will not do more harm than good whether it comes to the security of the nation or the reputation of good people.

No profession always meets its responsibilities or always meets them perfectly. Certainly not mine, and not yours either. There will be times, I suspect, when I will wonder again if I should have supported this measure. But I trust in your integrity and patriotism that those occasions won't be so numerous that I will, in fact, deeply regret my decision. And I would hope that when you do something controversial or something that many people find wrong and harmful you would explain fully and honestly how and why you did it, and confess your mistakes, if you made them, in a more noticeable way than afforded by the small print on a corrections page. In truth, the workings of American newsrooms are some of the least transparent enterprises in the country, and it is easy to believe that the press has one set of standards for government, business, and other institutions, and entirely another for themselves. And if you don't mind a little constructive cri ticism from someone who respects you, I think that is an impression the press should work on correcting.

Now, before I take your questions, I would like to respond briefly to the comments one of my opponents made the other day about the psychology and political mindset of Americans living in small towns and other areas that have experienced the loss of industrial jobs.

During the Great Depression, with many millions of Americans out of work and the country suffering the worst economic crisis in our history, there rose from small towns, rural communities, inner cities, a generation of Americans who fought to save the world from despotism and mass murder, and came home to build the wealthiest, strongest and most generous nation on earth. They were not born with the advantages others in our country enjoyed. They suffered the worst during the Depression. But it had not shaken their faith in and fidelity to America and its founding political ideals. Nor had it destroyed their confidence that America and their own lives could be made better. Nor did they turn to their religious faith and cultural traditions out of resentment and a feeling of powerlessness to affect the course of government or pursue prosperity. On the contrary, their faith had given generations of their families purpose and meaning, as it does today. And their appreciation of traditions like hunting was based in nothing other than their contribution to the enjoyment of life.

In my other profession and the war I served in, the country relied overwhelmingly on Americans from these same communities to defend us. As Tocqueville discovered when he traveled America two hundred years ago, they are the heart and soul of this country, the foundation of our strength and the primary authors of its essential goodness. They are our inspiration, and I look to them for guidance and strength. No matter their personal circumstances, they believed in this country. They revered its past, but most importantly they believed in its future greatness, a greatness they themselves would create. They never forgot who they were, where they came from, and what is possible in America, a country founded on an idea and not on class, ethnic or sectarian identity. And America must not and will not forget them.

Next week, I'll begin a tour of places in America that do not frequently see a candidate for President. They are places far removed from the prosperity that is enjoyed elsewhere in America. I want to tell people living there that there must not be any forgotten parts of America; any forgotten Americans. Hope in America is not based in delusion, but in the faith that everything is possible in America. The time for pandering and false promises is over. It is time for action. It is time for change, but the right kind of change; change that trusts in the strength of free people and free markets; change that doesn't return to policies that empower government to make our choices for us, but that works to ensure that we have choices to make for ourselves. For we have always trusted Americans to build from the choices they make for themselves, a safer, stronger and more prosperous country than the one they inherited.

Thank you.

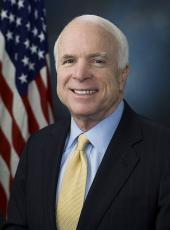

John McCain, Remarks to the Associated Press' Annual Meeting Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/277651