Today is a great day for Americans! President Obama and Secretary Kerry announced that the U.S. and Cuba have agreed to re-open U.S. Embassies that have been closed for over 50 years.

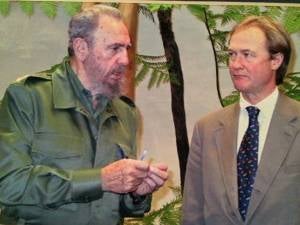

As a Senator, I had the opportunity to visit Cuba and meet Fidel Castro in January of 2002. It remains one of my most vivid memories of my time in the Senate.

Here is an account of the trip from my book, Against the Tide:

In January 2002, I went to Cuba with Senator Arlen Specter. The land has a unique topography; flat, green, and fertile in the west, stretching east into the towering Sierra Maestra, where Castro and his guerrillas operated in the revolution. I was struck by how the 745-mile-long island seems lost in time. Everything I saw there was modest and humble, but not what I could call poverty-stricken. No one appeared hungry, homeless, or sick; indeed, the island has far better health care and education than many of its wealthier neighbors. But it was a strange experience to get off a modern jet at José Martí International Airport and then share the road with horse-drawn carts on the drive into Havana. Many motorists drove fifty-year-old Soviet and American cars that ran on parts fabricated in backyard machine shops. Most buildings look as if they have not been painted since 1959, when Castro overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista and set up his own.

At night, the busiest streets in Havana are dark or dimly lit by a flickering streetlight or two. It is so unlike other capitals, where commercial districts shine bright with the effects of globalization, the neon signs that advertise the American consumer franchises spreading rapidly around the world. There is nothing like that in Havana.

In this totalitarian state, we were permitted to meet with leading dissidents working under the Varela Project, a movement to advance democratic political reform. They seemed a serious organization, but I wondered: Were they professional dissidents? Did the Communist government permit them to exist only as a public relations gesture to foreign critics?

At a state dinner, our gray-bearded host in his trademark military fatigues touted his country's low infant mortality, its high number of doctors per capita, and the literacy of the Cuban people. My snap impression of Fidel Castro was that he is smart, quick with a laugh, and has charisma. At the same time, I am well aware of his ruthless history. Senator Specter meant to say something provocative at dinner. He asked the president, "When are you going to have free elections here in Cuba?" Castro shot back, "You mean like in Florida?"

In the course of a boisterous dinner that went on for hours—ending at 3:00 A.M. —I asked the Cuban president, mischievously, whether he supported calls for an end to the U.S. embargo. Even conservative senators from farm states were working to normalize trade with Cuba in the interest of opening new markets for their crops. Votes to end the embargo were increasingly close. Was it a given that Castro supported these efforts? I was betting he did not. Ending the embargo imposed in 1962 would change the way he had done business for almost his entire reign. He knew what I was getting at: The embargo works for him in a perverse way. Having a reason to lash out at the United States has been his meal ticket with the Cuban people for a long time.

He dodged my question and zoomed off on a tangent that I no longer recall. But I was satisfied; by not answering my question, he had answered it.

It was clear to me that day in Havana that the rest of the world is far ahead of us in planning for the end of the octogenarian president's rule. Nations in Europe, Asia, and Latin America were positioning themselves to take advantage of trade in the next Cuba. There was slight evidence of a robust foreign invasion at the time, but it was starting.

Related Images

Lincoln Chafee, Chafee Campaign Press Release - Us-Cuba Ties: Embassies Re-open Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/312719